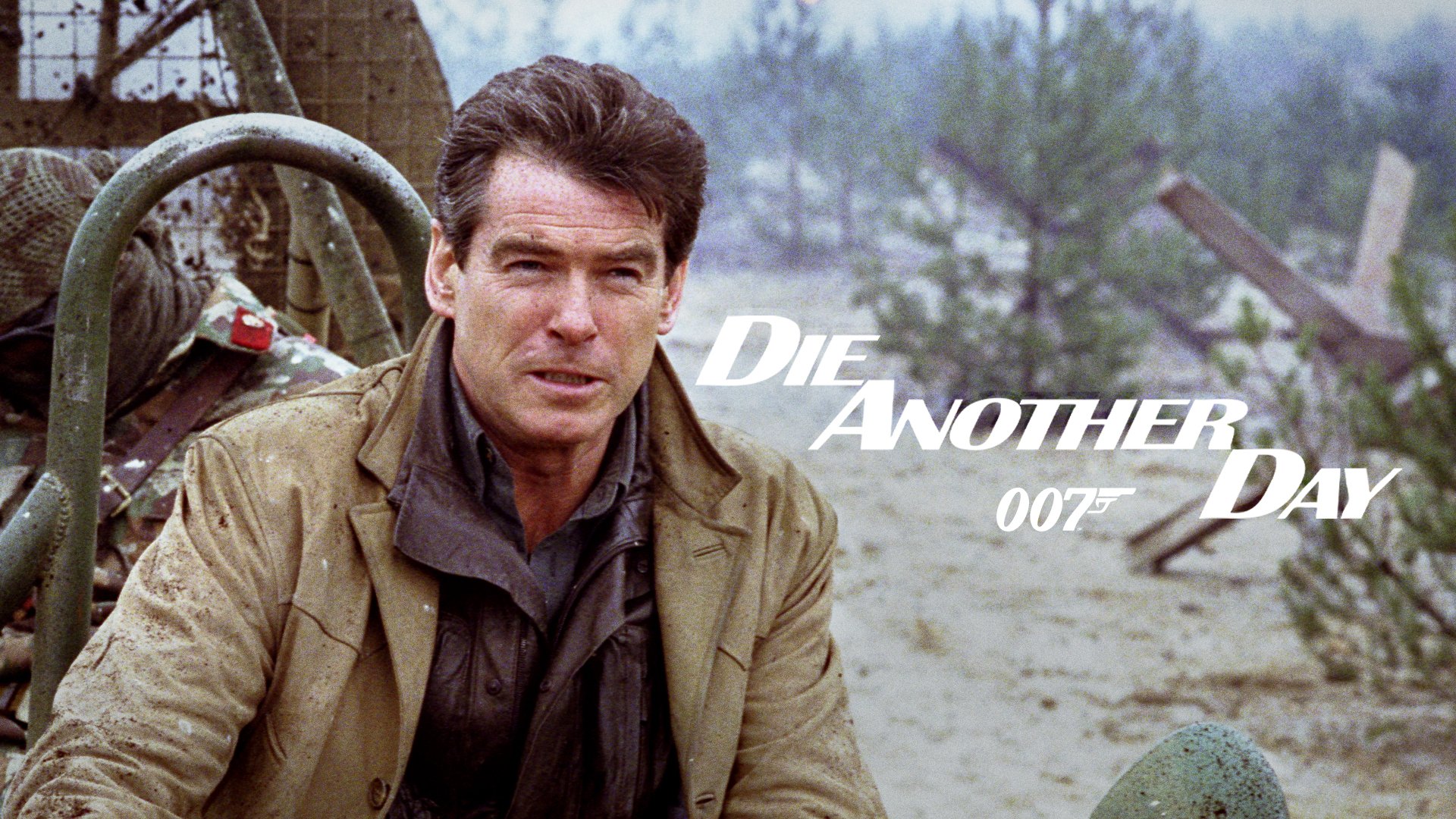

Beginner’s Bond: Die Another Day

“Beginner’s Bond” is a series of posts about closing the largest gap in my personal cinematic history: the James Bond franchise. I am watching all of the movies in order for the very first time and sharing my reactions here. Last time, The World Is Not Enough proved that the Pierce Brosnan era wasn’t all bangers. Hopefully he will get an appropriately heroic sendoff for his final tour in the trademark tuxedo: 2002’s Die Another Day.

007 is sent to North Korea to investigate a shady arms deal using conflict diamonds as currency. Of course his cover is almost immediately blown, resulting in a gunfight that leads to a silly hovercraft chase. Ultimately, Bond is captured by General Moon and thrown into a torture dungeon. The opening credit sequence’s visuals depict 007 struggling to survive months of “enhanced interrogation” by the North Korean military. While James Bond has been captured numerous times before, he always escapes rather quickly. This is the first time Bond has faced the reality of imprisonment in enemy territory, which could be an interesting narrative element if it wasn’t forgotten as soon as he puts on a clean shirt and has a shave.

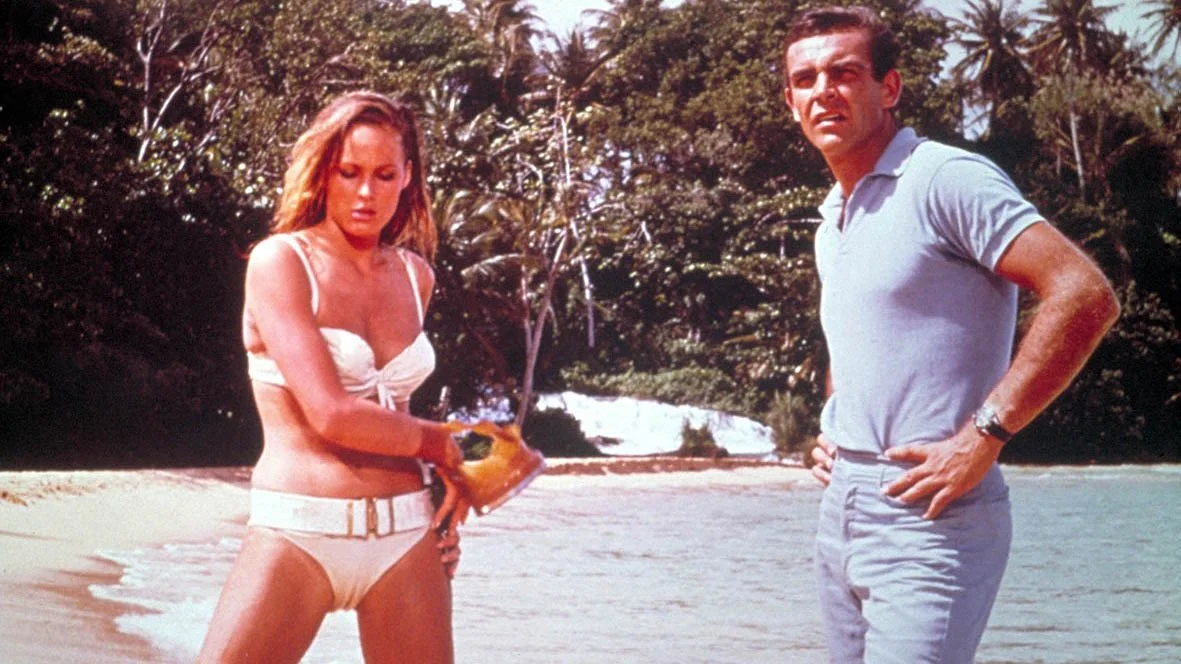

James Bond follows a lead to Havana, thankfully arriving just in time to see Jinx (played by Halle Berry) get out of the water. Her entrance and the design of her bikini pay homage to the very first Bond girl from Dr. No—Honey Runner, played by Ursula Andress. Unfortunately, it’s the most beautiful shot in this whole film. For the last twenty movies, cinema’s favorite secret agent has been traveling the world and bringing audiences gorgeous pictures of faraway places. So it is puzzling why so much of Die Another Day takes place in an ice palace that looks like a set built by a college theater company. While there is an impressive chase battle between two cars gliding on ice, most of the finale’s big set pieces are rendered entirely in primitive CG that looks like a cut scene from a PS2 game. The best fight of the whole movie happens at about the halfway point, when Bond engages Gustav Graves in an escalating sword duel. Just like Blofeld before him, Graves’ villainous plan uses diamonds to create a giant space laser that he will use to hold the world hostage. I believe that is the fourth space laser plot for the series.

Sadly, Die Another Day is just a straight-up dud. No fun, no excitement at all. The plot is contrived, driven primarily by coincidence rather than character action. It feels like pieces of several different scripts were stitched together to make this cinematic sleep aid. This movie made the same mistake as On Her Majesty’s Secret Service by including so many references to previous, better movies. Die Another Day did not fare well in the comparison.

Now that it’s all said and done, it seems like Pierce Brosnan just shone too brightly in his first two movies. The ones that followed simply couldn’t keep up. The Brosnan version of Bond was a synthesis of what had come before, perfectly splitting the difference between comedian and killer. It will be interesting to see how much 007 will change (or won’t) when Daniel Craig dons the tuxedo for the first time in 2006’s Casino Royale.

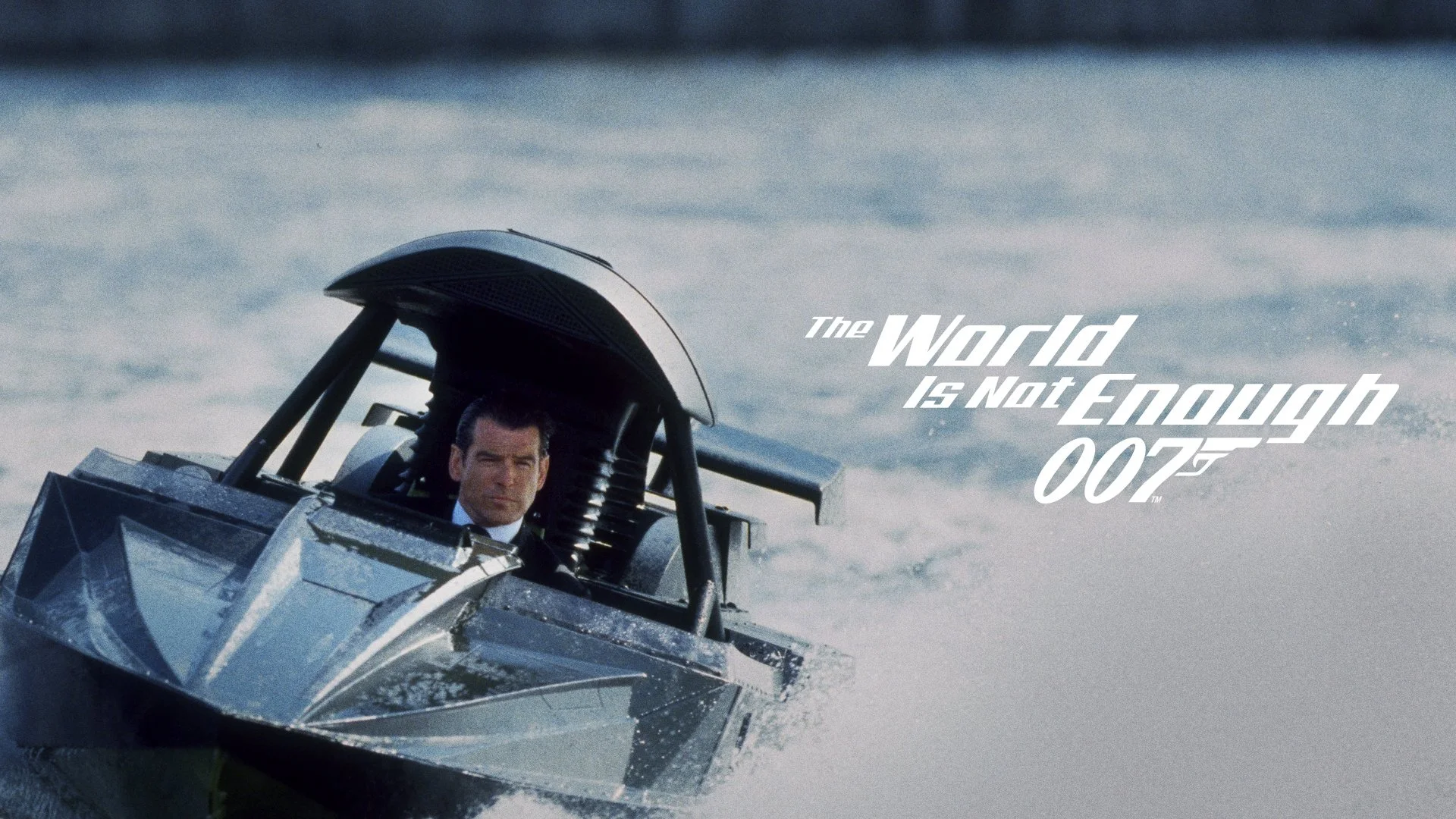

Beginner’s Bond: The World Is Not Enough

The “Beginner’s Bond” posts tell the tale of my quest to close the biggest gap in my personal cinematic history: the James Bond franchise. I am watching all of the movies in order (mostly) for the first time, and sharing my reactions here. Pierce Brosnan has been killing it as 007, with GoldenEye and Tomorrow Never Dies both being classic espionage thrills dressed up for the modern age. Is it even possible for 1999’s The World Is Not Enough to top that?

Not quite.

The world’s greatest secret agent is sent to retrieve a briefcase full of cash that was lost by a British oil tycoon who just happens to be old friends with M, which is an egregious abuse of state resources, but the movie must go on. The briefcase turns out to be a cleverly concealed bomb, and 007 has just delivered that gentleman his death. As such, his professional pride demands he kill those responsible. The trail leads him to Renard, a former KGB agent turned terrorist for hire. He has a bullet lodged in his skull from MI6’s previous attempt on his life. Although the bullet is slowly killing him, it has also negated his ability to feel pain. As a doctor explains, he will become stronger every day until he dies. The day he took that shot to the head, Renard was holding the tycoon’s daughter, Elektra King, for ransom. Fearing history might repeat itself, M tasks Bond with protecting Elektra. This inevitably leads to Ski Chase Number Six for the James Bond series as our heroes flee down a frosty mountain with heavily-armed snowmobiles in pursuit.

Elektra does a lot of very suspicious shit, like dropping a million dollars on a high card draw in a Russian gangster’s casino. Bond eventually discovers that she didn’t escape Renard all those years ago—she joined him. She’s actually his boss now, the architect of a terrorist plot on a far grander scale than Renard could have ever imagined on his own. They’re going to use a stolen nuclear submarine as a bomb to wipe out her main competitor’s pipelines; all of this sabotage is disguised as a singular hateful act by a random group of rogues. The series does not do plot twists often, and rarely well when it does, but this one was surprisingly effective. While there have been a few Bond girls who worked for the bad guys, Elektra is the first to also be the main villain.

Renard sounds like he would be a formidable henchman based on how all the other characters talk about him. But other than a theatrical demonstration at the beginning of the movie, his inability to feel pain doesn’t seem to provide him with any noticeable advantage. Renard doesn’t absorb damage with a stone face. He grimaces in what looks like pain and goes down when 007 punches him. Everyone says he’s super strong, but he never lifts anything particularly heavy or knocks anyone across a room.

Renard is just the most visible symptom of the biggest problem in The World Is Not Enough. This movie commits the cardinal sin of screenwriting: it does a lot of telling without an adequate amount of showing. There is no evidence of the impressive abilities other characters attribute to him. The film also tries to distinguish itself by giving James Bond a persistent injury, which I believe would be a first for the series. However, that injury only exists on paper that is literally discarded. The only potential problem posed by Bond’s injury is the possibility that he will not be declared medically fit for duty, an obstacle that evaporates the instant it’s revealed that the doctor examining him is a pretty woman. So James Bond goes into the field physically weakened—that could add an interesting layer to the story. But the effect is mostly cosmetic. For the rest of the movie, 007 will grimace and moan every time something twigs his hurt shoulder, and that’s about as bad as it gets. The pain never stops him from doing anything and his shoulder never gives out on him, so Mr. Bond may as well not be injured for all the difference it makes to the movie.

The World Is Not Enough has some fun action set pieces, but it simply can’t compete with its predecessors. It’s slower paced, less propulsive, the excitement is drip fed rather than gushing from the screen. This movie is neither good nor terrible enough to be memorable. The first disappointing miss for Pierce Brosnan’s Bond, but maybe he can bring it back for his last round in the tux: 2002’s Die Another Day.

Beginner’s Bond: Tomorrow Never Dies

“Beginner’s Bond” is about investigating one of the biggest gaps in my personal cinematic knowledge: the James Bond franchise. As influential as they are, I had seen almost none of them until now. I am watching all of the films in order (mostly) for the first time, and sharing my honest reactions here. GoldenEye revitalized the series for a new era of filmmaking. Can 1997’s Tomorrow Never Dies possibly follow that act?

In a word: yes!

Tomorrow Never Dies has a propulsive opening, and it just keeps building momentum from there. James Bond is spying on a terrorist arms bazaar on the Russian border, and some stuffy Navy admiral calls for a missile strike before it can be pointed out there are nuclear torpedoes in the blast zone. 007 makes some creative chaos by tossing around explosives, then uses the confusion to steal the jet carrying the torpedoes and fly it out of range just before the bazaar is annihilated. Cue title sequence.

It seems the Pierce Brosnan films are particularly good at cold opens, but the rest of Tomorrow Never Dies follows the same brisk pace, rarely slowing down to let the audience catch their breath. The villain, media baron Elliot Carver, uses a stealth ship and fabricated evidence as well as practical violence to orchestrate a conflict between Britain and China that could easily spiral into World War III. Agent 007 has 48 hours to investigate before the two fleets are within firing range of each other.

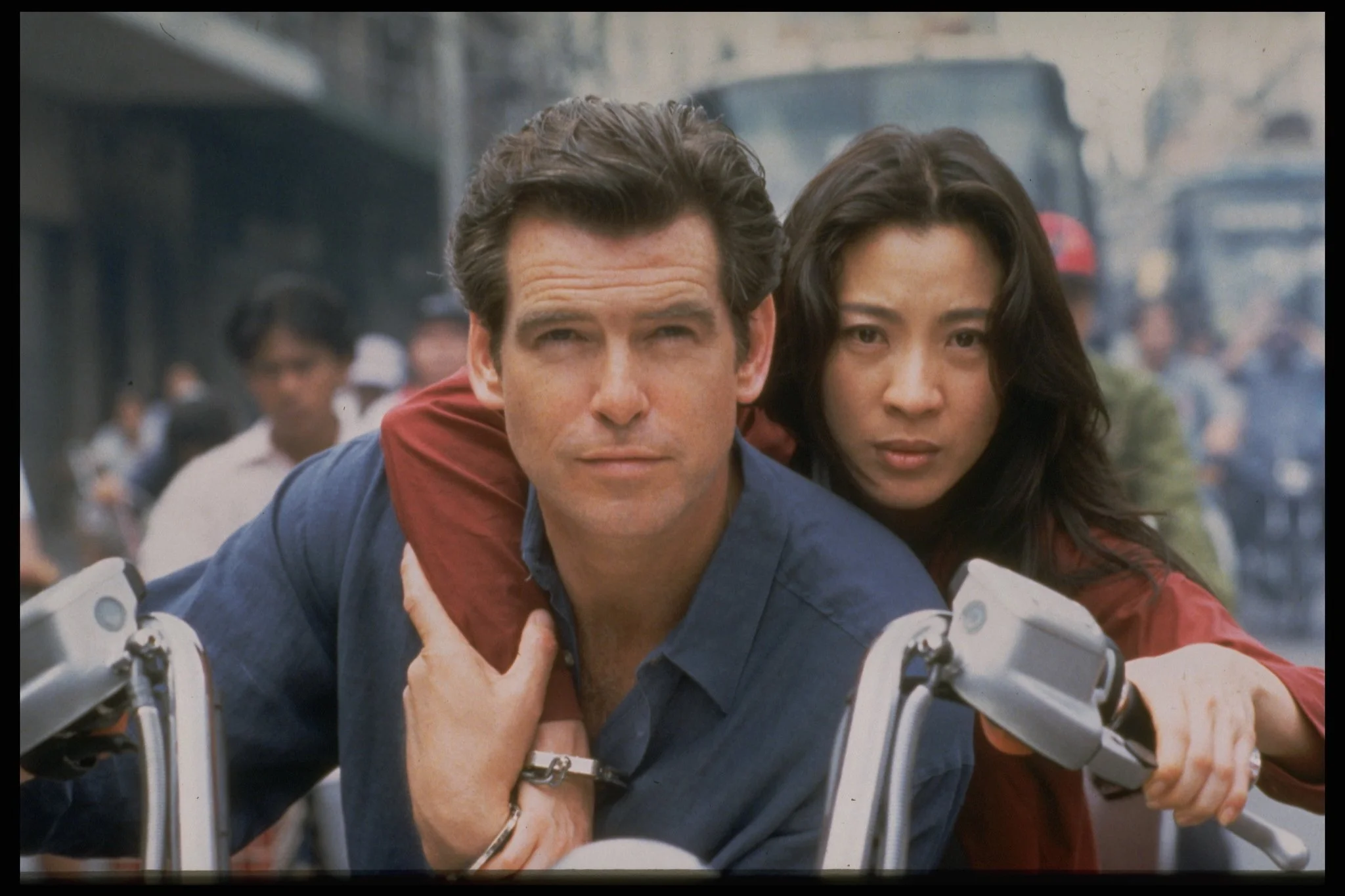

Since Carver was able to run news stories about the incident hours before MI6 found out, and also openly brags about taking bribes to increase or decrease the amount of coverage he gives a subject, Bond begins his investigation there. His cover is blown almost immediately, which leads to a gunfight at a newspaper facility, the death of the woman he seduced to gain access, and a rather clever twist on the traditional car chase that sees Bond controlling his vehicle and its many fun gadgets via his cellphone. He eventually joins forces with Wai Lin, a Chinese state security agent on the same case. And since she is played by Michelle Yeoh, she is a gifted ass-kicker that needs no help from a “decadent agent of a corrupt Western power.” They share a motorcycle as a helicopter chases them through Saigon, resulting in some award-winning stunt work that is still breathtaking to behold. Mr. Stamper, the uber mensch du jour, puts up a rather impressive fight, displaying both brains and brawn before ultimately being bested by Bond. But just like in GoldenEye before, 007 is able to kill all the bad guys and blow up the secret floating fortress before the marines ever arrive.

Of all the Bond villains I have encountered thus far, Elliot Carver is the most eerily prescient. His proclamation that information is the weapon of the future rings especially true in the year 2025, where media has become the modern battleground for cultural warfare. While Carver accurately predicted the ability of misinformation to manipulate entire nations, he could not foresee the death of truth. Today, Carver needn’t bother with all the stealth ship shenanigans. He could just run news stories about a conflict that never happened. As long as enough eyes see those stories, the lie becomes accepted and the falsehood is only strengthened by any contradicting evidence. An immoral media mogul of Carver’s stature could start a war from his iPad without ever going to the trouble of actually killing anybody—if he writes his stories the right way, the people will do it for him. That’s what makes him so much more insidious than previous villains—he’s not just murdering people, but convincing them to murder each other.

Didn’t anticipate this happening, but I think Tomorrow Never Dies might be better than GoldenEye. It’s faster paced with bigger and bolder action scenes, including some amazing stunt work, and it introduced the Western world to the magnificent Michelle Yeoh, the most memorable Bond girl yet. The villain has a timeless relevance, and it is a delight to watch 007 take him apart. Now I’m getting excited. Will The World Is Not Enough be even better?

Beginner’s Bond: Goldeneye

The “Beginner’s Bond” series of posts is a testament to my efforts to close the largest gap in my personal cinematic history: the James Bond franchise. I am watching all of the films in order for the very first time and recording my honest reactions here for your amusement. Today I’ll be talking about 1995’s GoldenEye, which debuts a new 007 played by Pierce Brosnan. Let’s see how he measures up against his predecessors.

The film opens with 007 running a co-op mission with his pal 006. They infiltrate a secret Soviet weapons lab and place some very familiar-looking mines all around it, but before Bond can hit the boom button, his buddy is captured by the enemy. Soviet Colonel Ourumov orders 007 to surrender, and when he does not comply, 006 is apparently executed. Bond blows up everything and makes a daring cliff-dive-into-a-falling airplane escape before we are treated to one of the more impressive title sequences of the whole series. The song “GoldenEye” performed by Tina Turner is one of the better themes, with thundering drums and bombastic horn stabs that make it sound almost like a cousin to the classic Bond theme.

Nine years later, James Bond fails to stop Xenia Onatopp, an operative of the Janus crime syndicate, from stealing a high-tech attack chopper during a demonstration. She and General Ourumov attack a radar station in Siberia, firing a Soviet orbital EMP weapon codenamed “GoldenEye.” Every electrical device for miles is wrecked, except for the chopper with its cutting-edge countermeasures, so Ourumov and Onatopp escape with all of the materials they need to fire GoldenEye again. 007 is sent to investigate, and that’s when things start going crazy. This movie has almost all the fun stuff you want from a James Bond experience—the corny puns, the classy outfits, the silly gadgets, the super strong henchman, over-the-top fights in difficult environments, and a chase scene with a ridiculous vehicle. Straightening his tie as he crashes through the streets of St. Petersburg in a tank is one of the most 007 images I can ever recall seeing—the wrecking ball in a three-piece suit. Natalya Simonova is an ideal Bond girl: beautiful and distressed, but not helpless. She’s actually integral to helping James figure out the plot. And Xenia Onatopp is a rarity among the pantheon Bond girls. She is the super strong henchman, as well as one of the few that never sleeps with James Bond.

Alec Trevelyan, the former 006, is one of the more fascinating villains of the franchise. He’s the first rogue agent we’ve seen from the 00 section, and his designation suggests he might be the equal of our favorite secret agent. Alec is ruthlessly clever, and quite skilled at solving problems by killing the right people…just like James. There’s also a petulant competitiveness in Alec's interactions with Bond, like an angry little brother desperate to prove he’s the best one. It’s not enough to just kill 007, he has to humiliate him first. Like many villains before him, 006 should have just pulled the trigger when he had his enemy at gunpoint.

Pierce Brosnan is the first actor to truly feel like he was succeeding Sean Connery. While Brosnan’s version of the character is obviously inspired by the original, he also borrows liberally from all the Bonds that came before him. Well, maybe not George Lazenby. Brosnan can hit the darker dramatic tones Timothy Dalton was striving for, but he is equally adept at the moments of broad comedy, delivering the humor without crossing over into the fully cartoonish like Roger Moore. Add in the weapons-grade charisma, and we have a James Bond for the post Cold War era. Pierce Brosnan’s performance successfully threaded the needle between the lighter and darker elements of 007. It’s no surprise that role made him a movie star and revitalized a franchise that many said had outlived its relevance. GoldenEye was also the first film to not use any plot elements from the original texts, proving that Agent 007 was not bound to his creator’s books, a character willing and able to face whatever adventure a writer can throw him into.

Full disclosure: GoldenEye is the film that introduced me to James Bond. I saw it in the theater when I was twelve years old. My mother took me to see it, and it’s the first time I ever recall her getting excited for a movie. It blew my tiny little pre-teen mind. At the time, I was pretty sure it was the best movie I had ever seen. Today it is still among my top three Bond films. And it would be impossible to overstate how influential the video game, 1997’s Goldeneye 007 for the N64, was on both me personally and games as a whole. I definitely wasted a lot of hours playing that game when I should have been doing homework. For a very long time, that was all I knew of James Bond: one movie, one video game, and a lifetime of secret agent jokes in cartoons and TV.

I was happy to discover that GoldenEye still held up pretty well. Even the rudimentary CG looks good despite being 30 years old. I’m genuinely excited to see the rest of the Pierce Brosnan era for the first time. Hopefully Tomorrow Never Dies (1997) will be an equally pleasant surprise.

Beginner’s Bond: The Timothy Dalton Experiment

The “Beginner’s Bond” series of posts follows my journey to close the largest gap in my personal film knowledge: the James Bond franchise. I am watching all of the movies (mostly) in order for the very first time and sharing my reactions. After 1985’s A View To A Kill concluded Roger Moore’s tenure in the tuxedo, it was time to pass the torch to a younger actor. Timothy Dalton took over in 1987’s The Living Daylights, and returned for Licence to Kill in 1989.

Although Timothy Dalton is one of the finest British actors of our day, he only played James Bond for two movies with terrible scripts, and thus his version of the character failed to distinguish itself from its predecessors in any positive ways. Since both The Living Daylights and License to Kill were bad in the exact same way, I’ve decided to roll them both up into one post.

The cold open of The Living Daylights has Bond and fellow agents 004 and 002 participating in a training exercise when an assassin disguised as a fellow participant kills several British agents and military personnel. That idea was interesting enough for an entire movie, but that’s just the first ten minutes of TLD. After taking out the assassin, Mr. Bond falls onto the yacht of a beautiful scantily clad woman who was literally crying out for a “real man” to fall out of the sky, and he seems barely interested. He makes a half-hearted quip, but I’ve never seen a James Bond less enthused by the prospect of spending time alone with a woman who is equal parts gorgeous and horny. That’s the real problem with this movie—James Bond isn’t having any fun. While he has always been depicted as devout in his duty, 007 also has a really good time getting drunk and laid while traveling the world on a government-sanctioned murder spree. But here the quips are flat and lame, and Mr. Dalton always looks so very serious. This version of 007 takes no pleasure in his work, which makes it that much harder to enjoy watching him do it. And it removes a great deal of the character’s charm.

Dalton was also paired with one of the worst Bond girls I’ve seen yet—Kara Milovy is nothing but a tedious burden the entire time, an albatross hanging around 007’s neck. She has zero agency, being passed back and forth between captors and rescuers like a football for most of the movie. When she is with Bond, she is not only completely unhelpful, but an active hindrance to the mission and a threat to her own safety. While a few Bond girls of the past were walking liabilities, they balanced it out by at least being funny, like when the air-headed Mary Goodnight accidentally hits the self-destruct switch with her butt. Kara is nothing but a needless nuisance, since ultimately her cello is more important to the plot than the woman who plays it.

Licence to Kill has an interesting premise: 007 resigns from MI6 in order to seek revenge upon the Colombian drug lord that killed his friend. The idea of James Bond operating off the reservation, on a personal vendetta without the support of his government, is intriguing. But this movie almost immediately ejects that notion. James still has access to plenty of weapons and intel, and Q even shows up to provide gadgets. So Mr. Bond isn’t really off on a solo revenge quest all by himself. There is no functional difference to the movie. We’ve also seen 007 pursuing personal vengeance before with Blofeld, so LTK doesn’t provide any of the interesting twists promised by the premise. It’s just another action thriller not doing anything terribly original.

Most confusing of all is that LTK has no idea how time works. It opens with Bond and his old CIA pal Felix Leiter on their way to Leiter’s wedding. They get picked up by a chopper en route because Franz Sanchez, the big drug lord Felix has been trying to put away, is in Florida. So they fly down to the Keys and engage in a long gunfight and chase sequence with Sanchez’s men before capturing the kingpin. The chopper drops James and Felix off at the wedding, which is still going on. The bride expresses her relief that the groom was “only a few hours late.” In the meantime, Sanchez is interrogated and prepped for transfer to prison. The transport carrying him is ambushed and Sanchez’s men orchestrate a complex underwater escape for their boss. Sanchez goes back to his house for a change of clothes and a cigar before setting out to take his revenge on Felix Leiter. Somehow he gets the home address of a CIA agent, so he and his men go over and find the happy couple still in full wedding dress, just about to call it a night. Which means this whole convoluted mess, from capture to escape to revenge, happens over the course of a few hours. Not even a whole day!

I don’t think Timothy Dalton was a bad James Bond. It just feels like he’s doing a completely different movie than everyone else involved. If Sean Connery’s Bond was the killer in gentleman’s clothing, and Roger Moore’s was a cartoon, then Timothy Dalton’s version is a Shakespearean tragedy. The very things that make James Bond entertaining to watch—the drinking, gambling, sex and violence—are also slowly destroying him. He is not the carefree killer playboy we’ve come to know over the last fifteen films, but rather a tortured assassin who often finds his conscience at odds with his duty. The movies try to split the difference between the classic camp and modern melodrama, and end up doing neither very well. No matter how sternly Mr. Dalton frowns, a chase down a snowy mountain (Number Five for the series!) using a cello case for a sled is just silly. You can’t take him seriously when he’s driving a car with lasers mounted in the hubcaps, because the world of this film is inherently ridiculous. It’s like an actor shouting Hamlet in the middle of a three-ring circus. The gravitas is lost beneath a cavalcade of clowns.

TLD and LTK are decent as generic espionage action thrillers of the 1980s, there’s little about them that is uniquely “James Bond.” No more gadgets, no silly names, no superhuman henchmen—no fun of any kind! By trying so hard to be “grounded and dramatic,” the filmmakers produced two really bland movies that vanish from memory as soon as the credits roll. These films aren’t bad, but they simply can’t stand toe-to-toe with the barrage of excellent action flicks that released in the same time period.

Up next on “Beginner’s Bond,” the movie that first introduced me to James Bond: 1995’s GoldenEye. I remember it being pretty good. Here’s hoping it holds up 30 years later.

Beginner’s Bond: A View To A Kill

“Beginner’s Bond” is a series of posts about my decision to finally close one of my largest blindspots in classic cinema: the James Bond franchise. I am watching all of the movies in order for the very first time, and recording my reactions here. Octopussy took 007 on a fun (if confusing) trip to India. Will 1985’s A View To A Kill provide a worthy finale for Roger Moore?

The movie opens with James Bond in Siberia, recovering a microchip from the dead body of Agent 003. And wouldn’t ya know it, some Soviet soldiers end up chasing him down a mountain on skis. To be fair, the movie does change it up a little by letting Bond lose his skis and have to improvise a snowboard. Although, it does play a Beach Boys song when he first masters the snowboard, which is just trying too hard to underline a joke that isn’t really there. The Bond movies have never relied on cute pop music needle drops, so it feels jarringly out of place here. Since this is ski chase number four in the franchise, I must concede that pursuits down snowy mountains are indeed a consistent element of the Bond mythos.

007 is sent to investigate some shady business going on at the horse track. Billionaire industrialist Max Zorin has horses that miraculously never tire and slow down, a distinct advantage in a horse race. A little intrusive snooping later, Bond discovers that Zorin is implanting his horses with devices that release adrenaline, giving the horse a significant boost on the final stretch without leaving behind anything that would show up on a drug screen. Now that I’ve written that out, it seems to me that—adrenaline or not—a horse is unlikely to run its best race after surgery on its leg. “Whatever!” A View To A Kill boldly declares, “That’s only the tip of this crazy iceberg!”

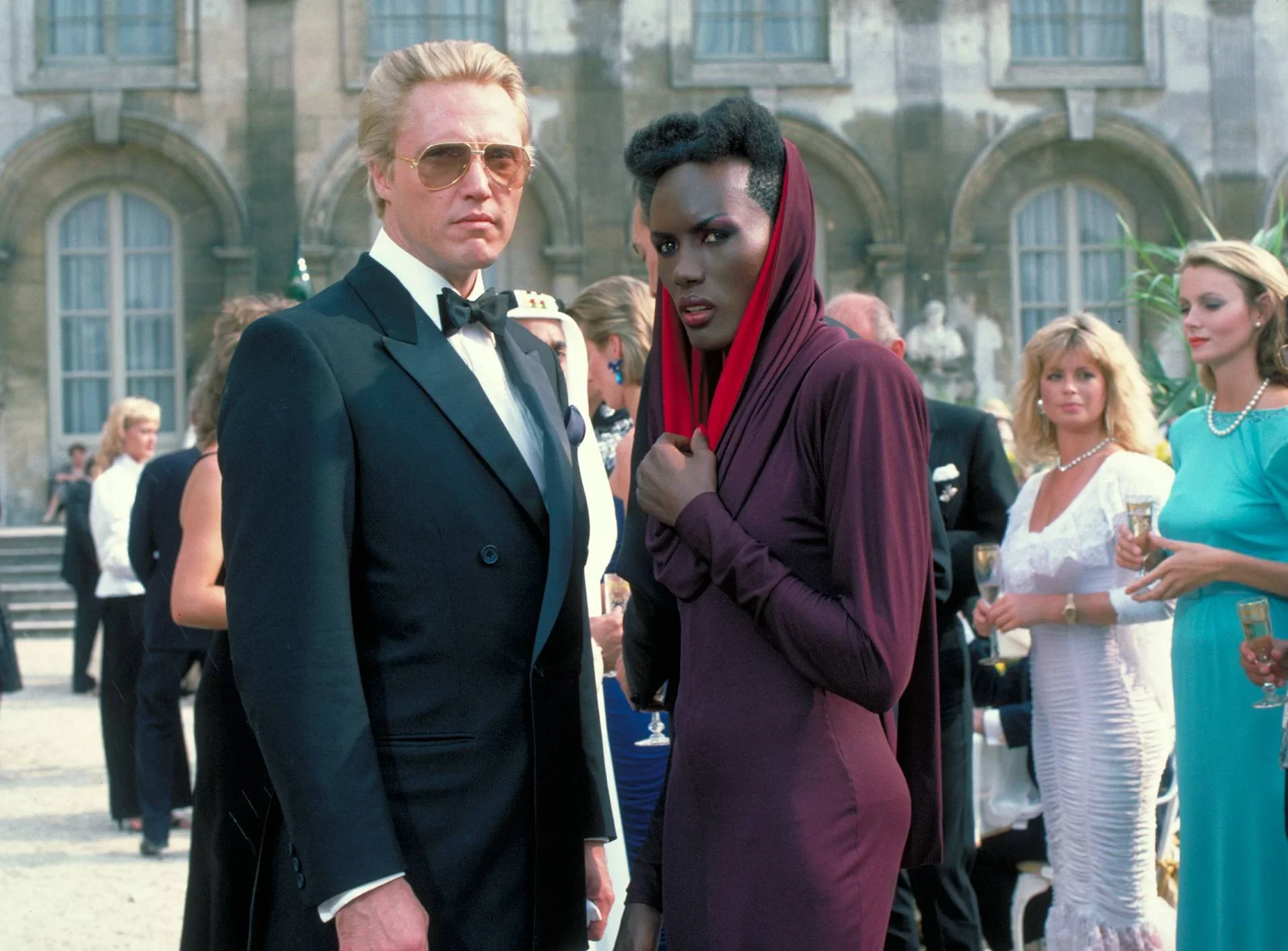

It turns out that torturing animals for money is the least of Mr. Zorin’s sins. He treats women like objects, verbally and physically abuses his employees, and murders potential business partners when they don’t accept his one-sided offer. Max Zorin delights in his own cruelty purely for the sake of it. On top of all that, it turns out he’s actually a deep cover KGB agent that’s gone off the reservation. Zorin’s got a crazy plan to blow up a fault line beneath California to trigger a massive earthquake that will fill Silicon Valley with seawater. With his primary competition drowned, Zorin will dominate the world market for microchips.

Honestly, capably delivered by Christopher Walken, the plan almost sounds crazy enough to work. He is unique among Bond villains because he genuinely seems to be enjoying himself. When Zorin looks up 007’s resume and sees “License to Kill,” he chuckles. He laughs the hardest when he drowns his workforce and guns down those that make it to shore. Another first for the series—Zorin’s bodyguard May Day (played by Grace Jones) is both a Bond girl and a superhuman henchman.

After a hilariously corny fight with an axe-wielding Max Zorin atop the Golden Gate Bridge, the age of Roger Moore finally comes to a close. With seven movies under his cummerbund, Mr. Moore is still the actor that portrayed 007 the longest. He was James Bond for several generations of young fans. Love him or hate him, that makes him an important part of the filmography. While I stand by my assessment that Roger Moore’s version is essentially a cartoon character, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Live and Let Die was a very bad movie full of very bad things, but the others, movies like Moonraker and Octopussy, are a silly good time. He may not be the most iconic Bond, but he seems to be having the most fun.

Next time on “Beginner’s Bond,” I will be introduced to Timothy Dalton’s version of the character from 1987’s The Living Daylights. Other than George Lazenby, he’s the Bond I’ve heard the least about, but I’ve enjoyed Dalton in many other movies, so I’m tentatively excited.

Beginner’s Bond: Octopussy

“Beginner’s Bond” is the chronicle of my quest to close the largest gap in my cinematic knowledge: the James Bond franchise. To that end, I am watching all of the 007 movies in order for the very first time and writing my reactions here. Due to a mistake on my part, the last film I watched was 1979’s Moonraker, which was a stupid good time. Let’s see if the film with the strangest title yet, Octopussy, can compare.

I gotta give Octopussy credit—it lets you know up front that this movie is going to be absolutely bonkers. It opens with a clown being hunted through the woods by a pair of knife-throwing twins. He gets stabbed in the back and literally crashes into some shocked British politician’s house to hand him a Faberge egg. And then as soon as James Bond takes a look at it he declares it a forgery. What? The film has been on less than five minutes, and my head is already full of questions that I must have answered. Starting with “Why did this clown sacrifice his life for a fake Faberge egg?”

Mr. Bond swaps the fake for the original during a live auction because he’s just that slick, and then engages in a bidding war to identify his target: prince-in-exile Kamal Khan. From there, 007 takes his usual approach by following the villain around and annoying him until the main henchman knocks out our hero and drags him to Khan’s palace. After escaping his room and snooping around, Bond learns that the prince has been using Octopussy’s traveling circus to smuggle stolen Soviet treasures into the West. Of course Octopussy decides to betray her business partner to help 007 about five minutes after meeting him, because no woman can resist James Bond.

Admittedly, I was unsure as to the specifics of the plot. A corrupt Russian general was smuggling jewels to Khan as payment for setting off a nuclear warhead on some European border for… reasons. Ultimately, I did not care because I was having too much fun. Octopussy pulls out all the classic Bond tropes. There’s a crazy taxi chase through an Indian market, a fight on top of a moving train with Gobinder the superhuman henchman, and 007 dresses up in a gorilla suit to infiltrate a circus. Octopussy leads her team of circus-trained ninja women in a final assault on Khan’s palace. It didn’t matter if any of it made sense—every scene you will see something more ridiculous than the last, and that can be plenty entertaining.

While Octopussy was certainly no masterpiece, it was never boring. I’d say this film and Moonraker are the best of the Roger Moore era thus far. But I’ll see if that opinion changes after I watch Mr. Moore’s final outing in the 007 tux: 1985’s A View To A Kill!

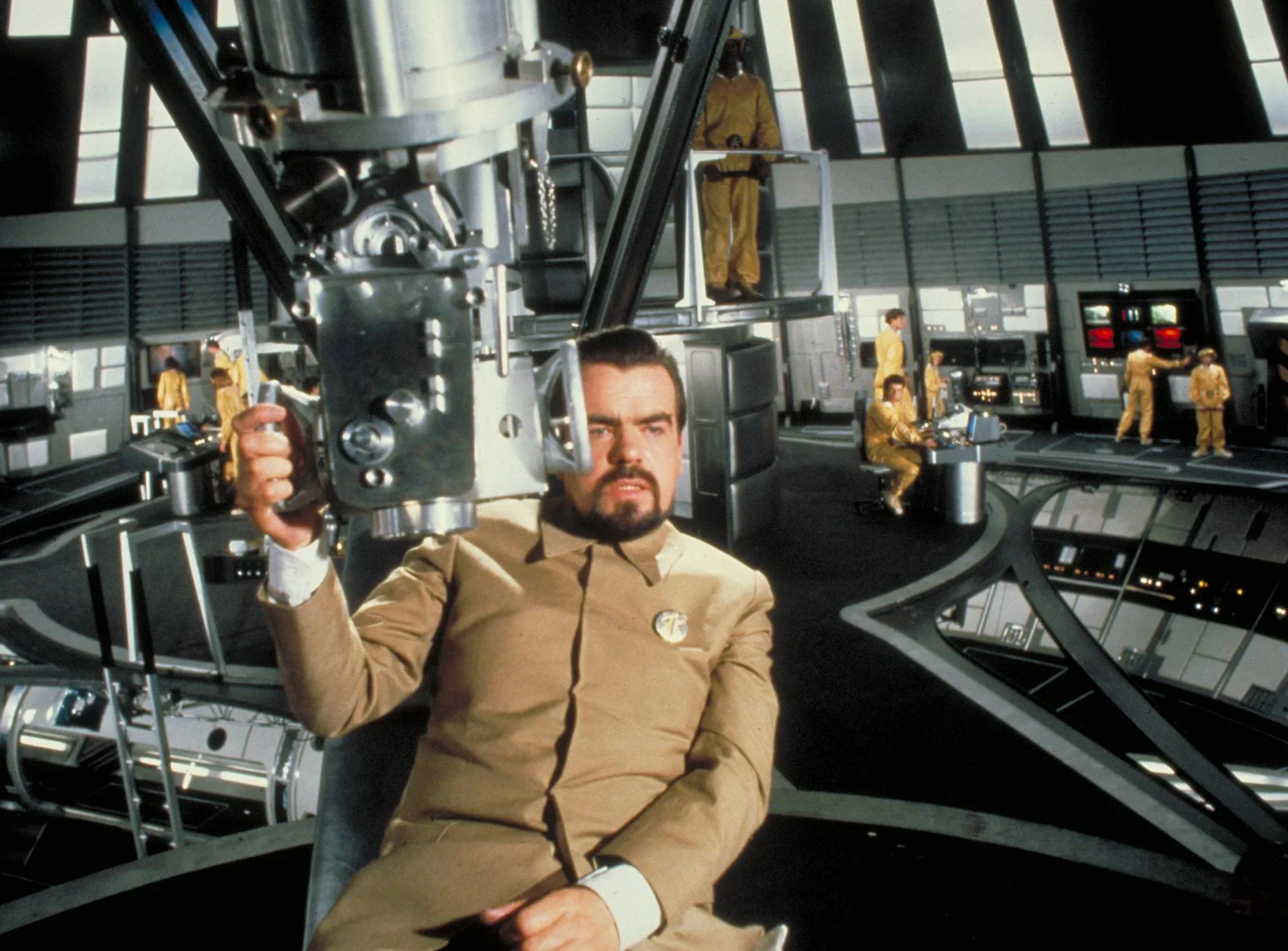

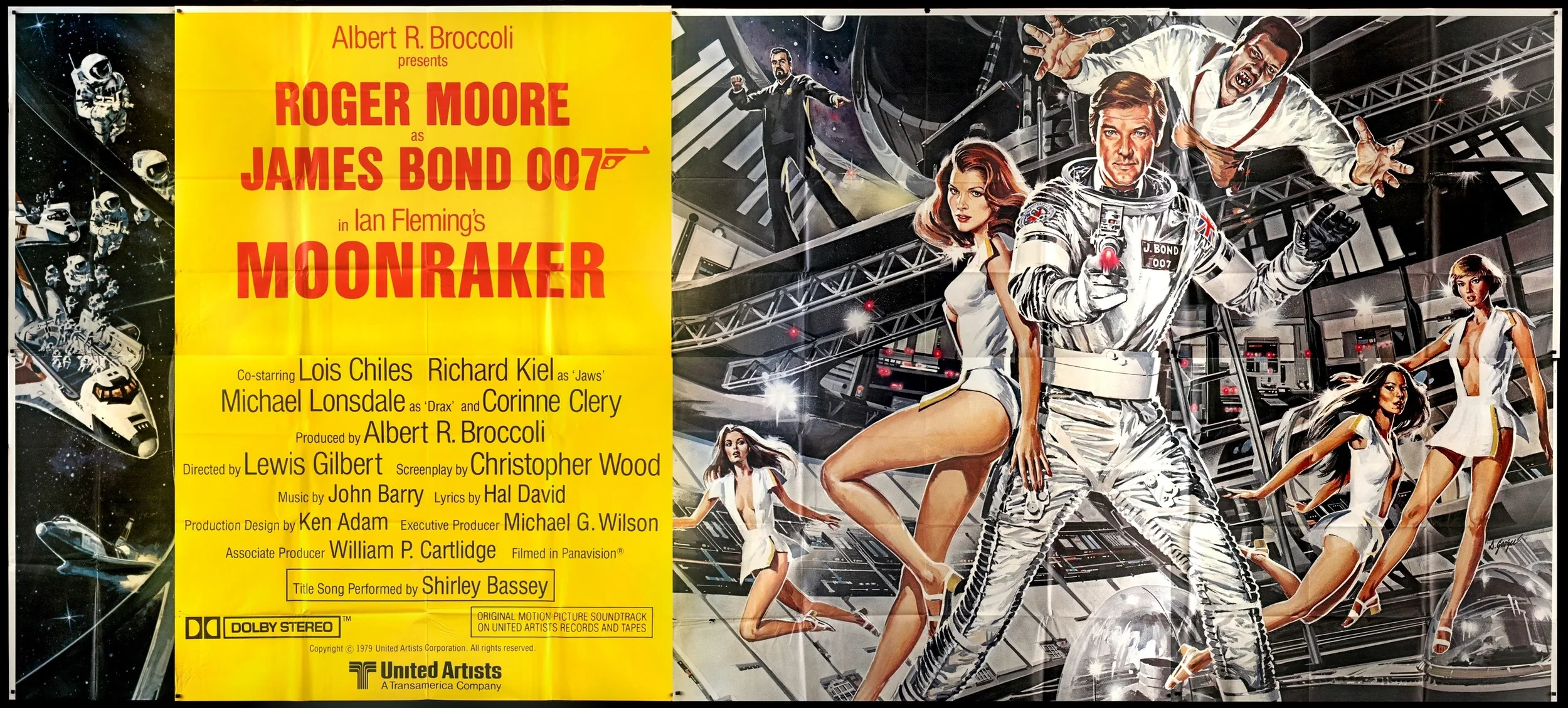

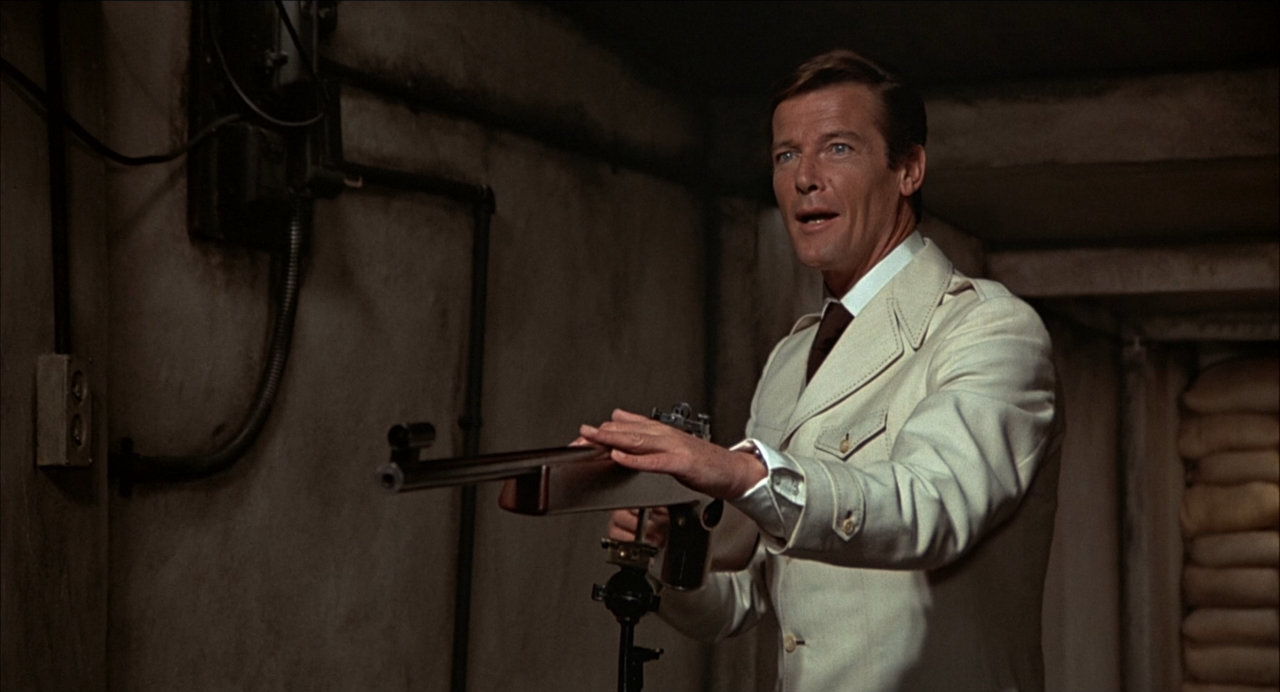

Beginner’s Bond: Moonraker

The “Beginner’s Bond” series chronicles my quest to close the largest gap in my personal film history: the James Bond franchise. I have been watching all of the 007 films in order… Well, I had been, until I got to here. When I reached the end of The Spy Who Loved Me, the next movie recommended by the Prime algorithm was For Your Eyes Only, which I foolishly assumed to be the next movie in the series. Why else would it be suggested to me at that moment?

I accidentally skipped over 1979’s Moonraker, but I’m really glad I came back for it. It’s definitely my favorite film from the Roger Moore era so far. This movie completely surrenders itself to the ridiculousness of a Saturday morning cartoon, and the result is a delightful sci-fi dessert of a movie. Not very substantive, but plenty of fun.

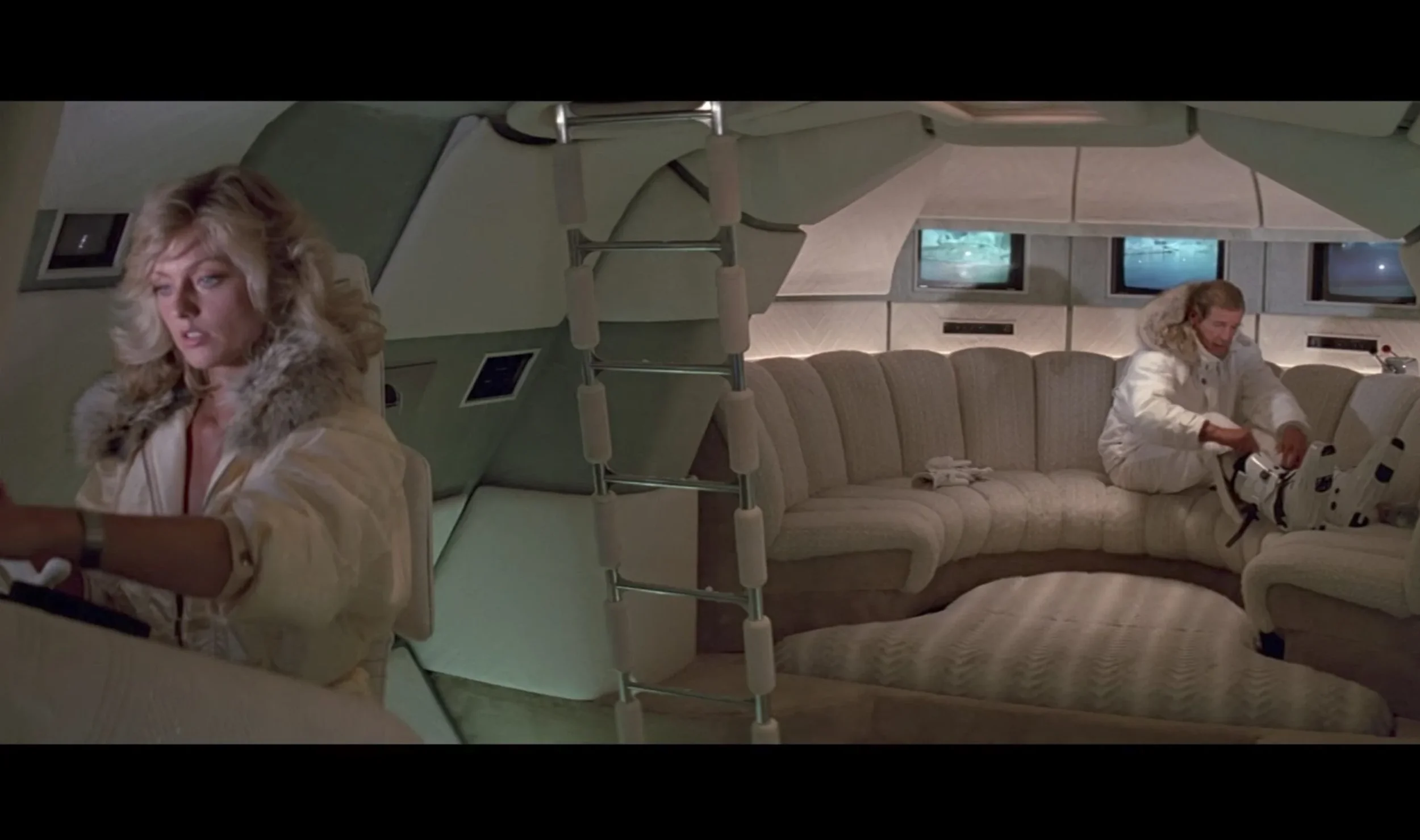

The title refers to a space shuttle that is hijacked in mid-flight and disappears without a trace. 007 is sent to investigate, and is almost immediately thrown out of a plane by Jaws. He wrestles a guy in midair to steal his parachute, a scene I have witnessed countless references to. Jaws survives the fall and is instantly smitten with a pretty girl that comes to check on him, an affection that seems to be reciprocated. When he shows up at Drax Industries asking questions, the villain attempts to murder Mr. Bond with a centrifuge. There are two delightfully ridiculous boat chases (one in a gondola!), a fight scene in a museum full of ancient glasswork waiting to be shattered, men getting defenestrated left and right—even a third act heel turn from Jaws. The series gets its second space station evil lair, and its third “exterminate humanity and start over” variety of villainous plot. We get to see a small army of armed astronauts assault a space station with laser rifles, and it’s a pretty awesome action set piece. Hugo Drax is such a creepy weirdo, a wannabe emperor with delusions of grandeur—being expelled into the void like debris is a fitting end for him. And just before the credits roll, we learn that Commander James Bond of Her Majesty’s Secret Service is the first man to get laid in space. Who else was gonna do it?

I still think James Bond is the most entertaining when he skates right on the edge of science fiction—two or three plausible but imaginative gadgets, maybe an impossibly well-armed vehicle, and the occasional jaunt into space. The promise is made in the very first scene, yet it never feels like the movie is in a rush to get there. It has plenty of interesting things to show you along the way.

Moonraker isn’t a brilliant film, but it is a good time. Up next is Octopussy, which wins the award for most bizarre title so far. I can’t wait (or am I terrified?) to find out what it means.

Beginner’s Bond: Copy & Paste

“Beginner’s Bond” is the chronicle of my quest to close the largest gap in my personal cinematic knowledge: the James Bond franchise. I am watching all of the movies in order for the very time and writing down my reactions. So far, the split on quality is about 50/50. We got five really good movies from Sean Connery, one ambitious-yet-boring one from George Lazenby, and two of the worst with Roger Moore. I sincerely hope Mr. Moore can break the trend since he ultimately has the most outings in the iconic tuxedo. Let’s see if he can turn it around in The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) or For Your Eyes Only (1981).

This is going to be another double entry, due to a small mistake on my part. While the intent was to watch all of the movies in order, Prime pulled a fast one on me. Once I had finished watching The Spy Who Loved Me, the “watch next” feature recommended For Your Eyes Only. I assumed that was the next movie in the series, because that is what would make the most sense. How foolish of me. Of course I will go back to watch Moonraker (1979) later, but this mixup proved surprisingly serendipitous. Watching TSWLM and FYEO back-to-back made it clear just how blatantly similar they are, as if the screenwriter of one was cheating off the other writer’s paper. Although historically impossible, it reads as if someone fed a Bond script into an AI and asked it to produce something familiar, but with just enough details changed to give the appearance of a brand new story. Human writers used to be able to cheat on their own; now we outsource it to a machine. It’s a shame, but that’s a topic for an entirely different article.

I’m going to describe the plot of a film. See if you can guess which one it is.

When an important government watercraft disappears, 007 is sent to investigate. He meets and teams up with a dangerous woman who is out for revenge. As they travel the world seeking their target, our heroes in love and are pursued by a superhuman henchman who survives multiple fatal situations. After a daring ski chase down a snowy mountain and some scuba-assisted sleuthing, Mr. Bond is eventually captured by the villain and brought to a secret fortress so that he can explain his evil scheme in detail. Naturally, the world’s greatest secret agent escapes, blows up the base, and still has time to get the girl before the final credits roll. Cut. Paste. Print.

Were you able to figure out which movie I was describing? Trick question. That paragraph is a an accurate summary of both movies. Before I realized my mistake, I was shocked that two movies in a row featured an extended set piece on skis. And now that I know, it’s still kind of silly that this series has had at least three big ski chases. I never knew that was such a recurring trope. But I guess Mr. Bond likes to hit the slopes just as much as the sheets. While I understand that all of these films follow a certain formula, and that’s a big part of the fun, this is the first time its felt like one movie was recycled from another.

One significant difference is the henchman employed— TSWLM introduced us to Jaws, a silent heavy so iconic that I’ve been seeing him alluded to and made fun of my whole life in countless cartoons, TV shows and movies. He was even a playable character in the landmark video game GoldenEye 007, which wasted countless hours I should have spent on homework in 1997. Seeing him in action was an absolute delight. By contrast, FYEO has Bond being hunted by a German biathlete devoid of any personality. Honestly, I don’t even remember how 007 killed him. But I’m crossing all my fingers in the hope Jaws will return for another round.

Roger Moore does a much better job when he’s not saddled with one of the franchise’s worst scripts. His version of James Bond is clearly more of a lover than a fighter, achieving most of his mission objectives through the use of seduction and subterfuge. But even when he’s shooting people and throwing knives, Mr. Moore doesn't capture the killer’s edge that Sean Connery brought to the character. This iteration of 007, the debonair gentleman gambler who knows everything, never misses a shot, and gets every girl—he’s a cartoon. A caricature of the secret agent man archetype established by this very franchise. James Bond has literally become a parody of himself. In any other context, that would be a pretty savage burn, but that’s not what I mean. Roger Moore’s portrayal of 007 isn’t worse, it’s just different. His James Bond is more of a comedian than an action hero. Not a revelatory performance, but serviceable. Fun enough.

Next time on “Beginner’s Bond,” I have to double back and watch 1979’s Moonraker. If this movie opens with another intense ski chase, I’m going to be concerned. I never knew skiing was such an important part of espionage. From what I can tell, Moonraker appears to be set in outer space, so it’s unlikely there will be any snow. But I’ve certainly learned by now that nothing is impossible when it comes to James Bond.

Beginner’s Bond: Intro to Roger Moore

“Beginner’s Bond” is the tale of one movie nerd trying to close the largest gap in his cinematic knowledge: the James Bond franchise. I am watching all of the films in order for the very first time, and leaving my thoughts on each one here. Diamonds Are Forever reminded me of what a good 007 movie looks like, and I’m curious to see how Roger Moore fares in the iconic tuxedo.

However, today’s post is going to be a little different. This time, I’m going to cover two movies at once—Live and Let Die (1973) and The Man With The Golden Gun (1974). Sadly, both are pretty bad movies for many of the same reasons, so I don’t want to belabor the point with two whole posts about the same thing.

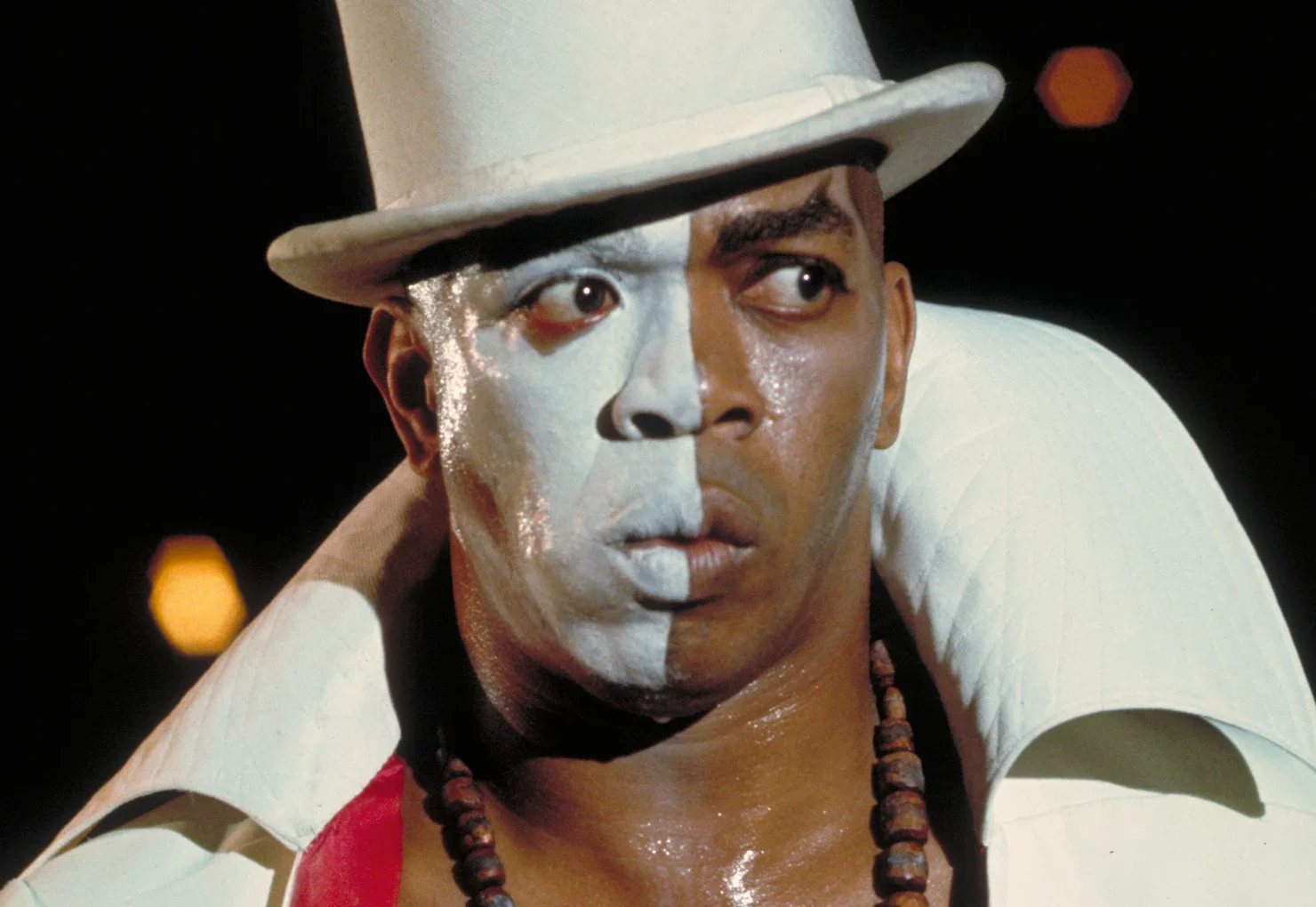

The best part of Live and Let Die is the title sequence, featuring the song of the same name by Paul McCartney and Wings. This is the first Bond theme I had heard on the radio and in other movies when I was growing up. I never knew it was a James Bond song—thought it was just another cool psychedelic rock track. Unfortunately, once the opening credits conclude, it all goes downhill with impressive speed. The film “borrows” inspiration from the blaxploitation genre that was popular at the time, and ends up creating the most racist Bond movie I have yet seen. MI6 sends 007 to Harlem to investigate the deaths of multiple agents under mysterious circumstances. His investigation leads him to Mr. Big, who isn’t a megalomaniacal supervillain so much as a really shrewd drug kingpin. He’s not trying to take over the world with a death ray; Mr. Big just has a fairly clever plan to corner the heroin market and get rich. With one exception, every single black person James Bond encounters in this movie works for the bad guys. Every cab driver, cook or cop—an entire congregation performing a fake funeral march in New Orleans to secretly remove corpses from the street. Even poor Rosie Carver, the first African American Bond girl, turns out to be a double agent employed by Mr. Big. Voodoo beliefs and practices are depicted as black magic used by a cult of criminals who gather to do tribal dances in traditional dress while performing the ritual sacrifice of a white woman. James Bond’s distaste for this “strange” culture is regrettably pronounced. He looks utterly disgusted by everything he sees in this film, unable to believe people really live this way. And to mention the obvious, the very white, very British man James Bond is the worst spy you could assign to infiltrate Harlem or New Orleans. He does not escape notice.

The Man With The Golden Gun is more entertaining than its predecessor. While it demonstrates a profound ignorance of Asian cultures (particularly around martial arts), it’s not as egregiously offensive as Live and Let Die. I counted at least four Chinese characters that were good guys, which is a small but significant improvement. In this film, 007 meets his match: Francisco Scaramanga, an assassin of incomparable skill who always kills his targets with a single golden bullet fired from a matching gun. Scaramanga is actually a fan, considering Mr. Bond his only true equal in the field of violence. In pursuit of his quarry, 007 follows the trail from Macau to Hong Kong, and then on to Thailand. Throughout the journey, different peoples and cultures of Asia are treated as basically interchangeable. James is captured and taken to the enemy’s karate school to fight its students in death matches, which makes no cultural sense. Karate is Japanese, and so at the time it was vanishingly unlikely there would be a functioning dojo in Thailand. Muay Thai is the native martial art of Thailand, yet the students use moves and forms that are neither. Apparently an army of killers is trained here, but when James kicks the asses of their two top students before making his escape, aided by the Hong Kong cop and… his nieces that he’s picking up from school? The cop uses kung fu, while his nieces use wuxia-style moves more suited to stage fighting than real combat. Whatever move the enemy does has to be very broad and slow so that Roger Moore can actually block it and counterattack. As a result, the movie manages to make martial arts training look like a liability in a fist fight. Which is such a strange deficiency to find in a film that is clearly inspired by Bruce Lee’s kung fu masterpiece Enter the Dragon, which had released the previous year. But at least The Man With The Golden Gun doesn’t cast an entire race of people as evil.

Unlike its predecessor, The Man With The Golden Gun has a few highlights that make it easier to watch. Christopher Lee’s portrayal of Scaramanga is fantastic despite a deficit of worthy material to work with. At the end of the movie the script just staples a generic death ray plot onto a villain not suited to it, but Scaramanga’s childish delight at getting to play cat and mouse with the object of his admiration is infectious. It’s also fun for the audience to watch a character that is capable of outsmarting and manipulating James Bond. For the first time, our favorite secret agent spends most of the film on his back foot. This movie also contains one of the most perfectly-executed practical car stunts ever captured on film, a corkscrew jump off broken bridge with a flawless landing. Bumps Willert, the stunt driver, nailed it on the first try. He got a standing ovation on the set and a $30,000 bonus, both well-deserved. But the director put a slide whistle to the scene, which undercuts the awesome stunt that just happened and turns it into a cartoon.

Finally, let’s talk about the man of the hour. Roger Moore—is he James Bond?

A tentative yes. Moore clearly isn’t trying to imitate Sean Connery. He’s trying to build his own version of Bond, and it has potential. This version of 007 is extra campy, addressing more one-liners to the camera than either of his predecessors. Moore is certainly adept at playing the dashing debonair gentleman part, but this Bond is a cold and calculating sociopath compared to Connery’s restrained killer. He wields violence like a scalpel, not a hammer. The flaw in the performance is that Moore plays Bond as too unflappable. There’s no threat that can’t be dismissed with a brief witticism, and it gets difficult to escalate things in the third act when the main character has the same blasé reaction to extrajudicial murder as he does to champagne that hasn’t been properly chilled. The audience isn’t going to believe the stakes are raised if the hero still hasn’t raised an eyebrow. I don’t need to see James Bond have an emotional meltdown, but he should have more than two reactions to pick from in every situation. If 007 looks bored with the whole thing, the audience will be too.

So Roger Moore wasn’t that bad, despite being given two of the worst scripts in the series. I’m willing to give him the chance to really explore the character and refine his performance. All that is to say… I really hope The Spy Who Loved Me isn’t this bad. Maybe it’ll just be cheesy and outdated instead of outright offensive. Fingers crossed.

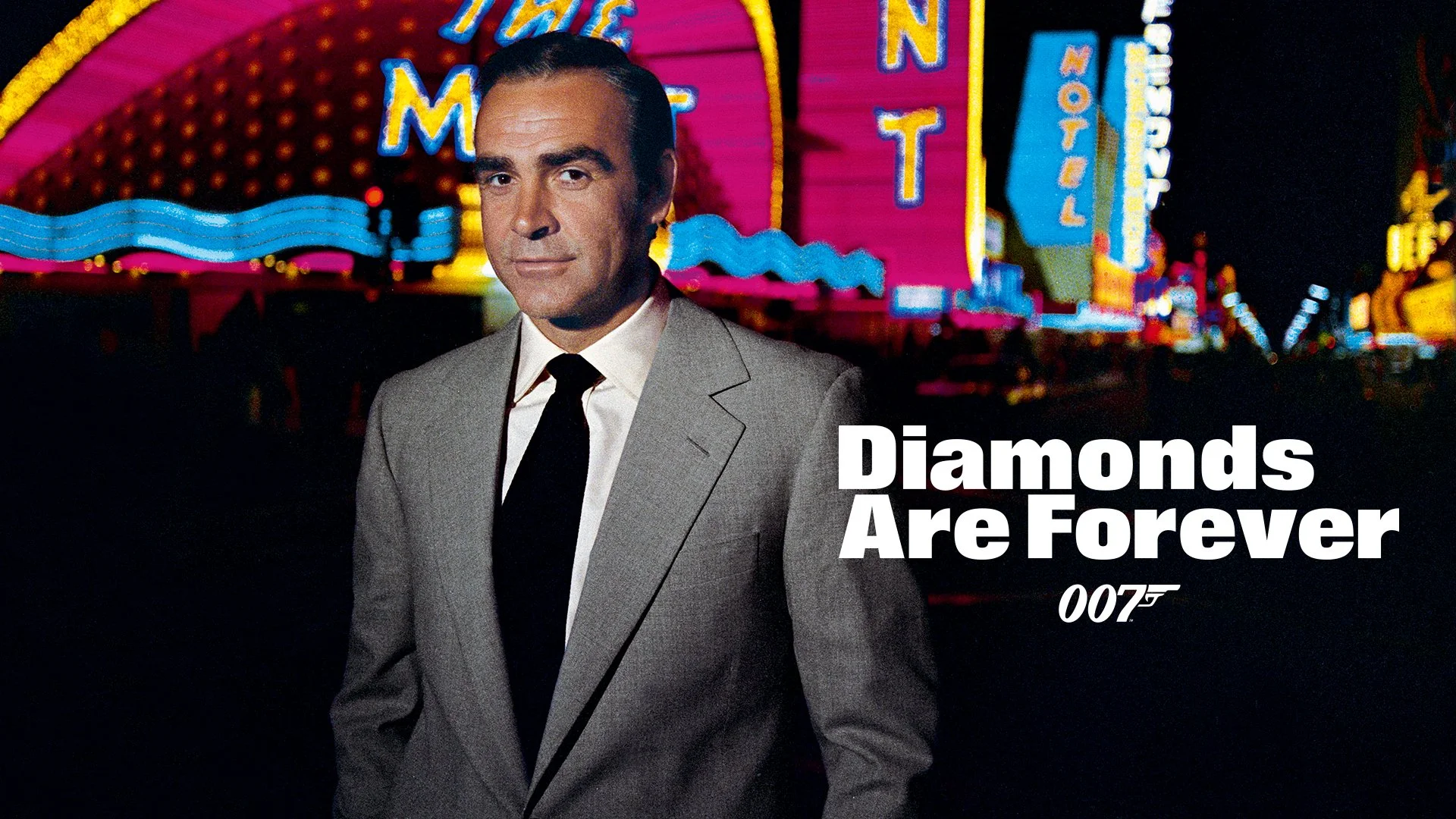

Beginner’s Bond: Diamonds Are Forever

“Beginner’s Bond” is about my quest to close the largest gap in my personal cinematic knowledge: the James Bond franchise. I’m watching all of the movies in order for the first time and recording my reactions here. Our last subject, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, was the first true dud of the series—I had to split up my viewing because I kept falling asleep. Let’s hope Diamonds Are Forever is nothing like it.

First and foremost, Sean Connery is back. It speaks to his prowess as an actor that the film is so drastically improved simply by putting him back in the role. Every scene is at least three times as interesting as anything that happened in OHMSS. That’s the quality that turns an actor into a bonafide movie star. You hear his voice before he ever appears onscreen, and a wave of excitement hit me as soon as I heard it. On an instinctual level my brain was saying “Yes! This is gonna be good.” There’s a reason the studio was willing to pay $1.25 million to get him back, which was the most a screen actor had ever been paid at the time.

The movie begins with 007 trotting the globe, following Blofeld’s trail, and he is not fucking around. The sequence is immediately compelling because (up to this point) we have rarely seen Mr. Bond so enraged that his human mask slips and we see the coiled violence beneath. He doesn’t even try to seduce the half-naked woman that has the intel he wants, which would typically be his first approach. Instead, he skips straight to literally choking the answer out her. When he finally catches up to the object of his hatred, Ernst Stavro Blofeld, he doesn’t kill him quickly. No, Mr. Bond decided to drown him in goo. He spent time and effort making his enemy’s final moments as agonizing as possible. While James has always had a rather cavalier attitude about killing people, I don’t think I’ve seen him be so intentionally cruel before. That’s where we get some of our truest insights into a character—when they do something that is unusual for them.

M orders Bond to investigate a diamond smuggling ring, suspecting that the culprits intend to manipulate prices by dumping. 007 fakes his own death (the second time) in order to infiltrate the smuggling operation. While he chases rumors of diamonds around, a creepy pair of assassins, Mr. Wint and Mr. Kidd, stay just a few steps ahead, eliminating every link in the smuggling chain. Of course, James’ investigation leads to a casino, then to an eccentric billionaire that turns out to be a front for his old pal Blofeld. Apparently Mr. Bond merely drowned his body double at the beginning of the film. Blofeld eventually reveals his plot, and I believe this is the first instance of a villain holding the world hostage with a space laser, a trope that became so popular it’s practically a cliche now.

All in all, Diamonds Are Forever is a fun return to form for the franchise. It has almost all the big hits: sci-fi gadgets like the voice changer, numerous overcomplicated impending death traps, beautiful women with silly names like Tiffany Case and Plenty O’Toole. And while Mr. Wint and Mr. Kidd are not superhuman, they are interesting enough characters to compensate. A pair of proficient killers who enjoy their work and love to make belabored puns about death—Mr. Bond was essentially fighting two extra crazy versions of himself. And once again, Sean Connery gives a masterful performance of a man who is as dangerous as he is charming. This movie is everything that is fun about James Bond, just more of it. I wonder how the next film, 1973’s Live and Let Die will measure up. Roger Moore has some pretty big shoes to fill, and I hope he’s up to it!

Beginner’s Bond: On Her Majesty’s Secret Service

These “Beginner’s Bond” posts are an account of my quest to close the largest gap in my personal cinematic knowledge: the James Bond franchise of films. I am watching all of 007’s adventures for the very first time and recording my reactions here. This time I’m in for something a little different with the 1969 movie On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

The film opens with our hero rushing into the ocean to save a woman attempting suicide by beach. The distressed lady is Contessa Teresa “Tracy” Vincenzo, who just happens to be played by Diana Rigg, one of the most beautiful women of ‘60s cinema. So she’s obviously the love interest from scene one. Bond gets kidnapped, the first of many times this will happen in the movie, and brought before Marc-Ange Draco, the kingpin of a massive European crime syndicate. He offers James a million dollars to marry his daughter, Tracy. Mr. Bond counteroffers that he will continue to see Tracy if Draco will help him track down Ernst Blofeld, the leader of the terrorist organization known as SPECTRE—which also happens to be the biggest competitor to Draco’s crime syndicate.

Blofeld’s villain lair is disguised as a research facility atop the snowy mountain of Piz Gloria. In order to infiltrate, Mr. Bond goes undercover as Sir Hilary Bray, a genealogist with the London College of Arms. This is because despite all of his wealth and power, Blofeld still covets the title of Count, as if that would finally make him a respectable gentleman. The wannabe count who claims to hold the world in his iron fist is still desperate for recognition from the kind of people who do not care about anyone outside their social strata. Even holding the power of life and death over every living thing on Earth, Blofeld is nothing so much as he is pathetically lonely, willing to kill millions people just to get the attention of elitists who will never see him as an equal no matter how many titles he manages to accumulate. It’s honestly the first time I found a Bond villain more pitiful than hateful, and that’s really no fun.

The longest Bond movie ever, clocking in at just under two-and-a-half hours, concludes with a big set piece shootout at a snowy mountain base—proof positive that OHMSS is definitely Christopher Nolan’s favorite Bond movie. That setting has been practically cut & pasted into Inception. There’s a thrilling chase on skis, and at one point Bond looks super cool firing a machine gun while sliding on ice, but all the energy and excitement built up from the big bombastic action sequence completely deflates as Bond and Blofeld look like toddlers wrestling in a runaway bobsled against the most obvious blue screens.

Director Peter Hunt removed a lot of the more fun elements established by earlier entries in the franchise—there are no sci-fi gadgets, no Aston Martin with machine gun headlights, and no superhuman henchman to defeat. And yet despite going to great pains to remove all of these “silly things” from his vision of James Bond, the movie continuously calls back to its predecessors, reminding the audience over and over again that these films used to be a lot better. There’s actually a scene where Mr. Bond takes some of his classic gadgets out of his desk drawer and stares at them with sentimentality as the themes from previous (much better) movies play. This and a few other mistakes were made with the intention of creating a continuity of character, so that viewers would know that this new actor was still playing the same James Bond they have come to know and love over the last five films. Except it did the exact opposite, showing us all the cool stuff 007 movies used to do before Peter Hunt decided to throw them out in pursuit of his vision of a slower, more boring Bond movie with enough blank space to take a nap and not miss any of the action. The misguided Mr. Hunt often made a big deal out of how “accurate” his adaptation was to the novel, including every single event from the original text regardless of narrative necessity. But there are no prizes for accuracy in filmmaking, nor any penalties for cutting out tedious wastes of time. A slavish recreation of the source material has never been a reliable indicator of a good movie, and that has not changed over the last fifty years.

The biggest and most obvious departure from what came before is that Sean Connery is not playing James Bond this time. For the sixth movie in the series, they decided to replace one of the most charismatic actors in the history of film with George Lazenby—an Australian model who had no acting experience, training, or talent. While he is effortlessly affable for most of the movie, that’s his only mode. Being friendly and likable is enough to make it through a photo shoot or a cocktail party, but Lazenby never gives the impression of coiled violence that simmered beneath Connery’s every scene. The original Bond was a killing machine that simply performed humanity in order to go undetected—he may play the boozy playboy as a cover, but he has no hesitation dropping all pretense of fun when it’s time to go to work. Lazenby’s Bond is just on a Swiss vacation—his natural charm works in scenes where Bond is socializing with the upper crust in their mansions and casinos, but his demeanor never changes. This version of Bond blows his cover because he can’t stop sleeping with all the pretty ladies employed by the bad guy, which just makes the character look stupid. Did he really think he could bang his way through the entire staff without Blofeld hearing of it?

The worst outfit James Bond has ever worn

OHMSS does an impressive job of making a conventionally handsome man look absolutely terrible for the majority of the movie’s runtime. Like the obvious attempt and failure to cover a mole on his chin with makeup that only draws more attention to what they were trying to hide. The costume department must have been holding a contest to dress their star in the ugliest outfits they could devise. One scene in Blofeld’s office has 007 dressed head to toe in beige polyester—he practically disappears into the room’s decor. The action scenes look like bad slapstick rather than professional violence, even by the standards of 1969. The moment when Bond snaps at his commander for taking him off the case falls completely flat as Lazenby, who is supposed to be losing his temper and telling his superiors to go screw themselves, looks more like he is struggling to hold in a fart until he can leave the room. During the section of the movie where Bond infiltrates the Piz Gloria facility under the guise of Sir Hilary Bray, Lazenby’s voice is dubbed over by another actor because he was incapable of performing the most basic foundational element of acting: talking like another person.

James wondering if he can hold that fart until the meeting is over

Honestly, even though George Lazenby was the biggest glaring flaw in a film full of them, none of it is really his fault. It was a bad idea to hire a guy with no acting aptitude at all to follow up a role that was originated by one of the most charismatic movie stars to ever grace the silver screen. Tossing Lazenby in the deep end with no lessons or coaching was a worse idea. Throwing away all the fun stuff that was in the James Bond toy box and calling attention to the absence multiple times is one of the most puzzling unforced errors to be found in fiction. Nothing was broken, but Peter Hunt decided he had to “fix” it all anyway, and the result is the dullest 007 flick yet, the first in this series to make me fall asleep. Hopefully things will look a little brighter with the return of Sean Connery in Diamonds Are Forever.

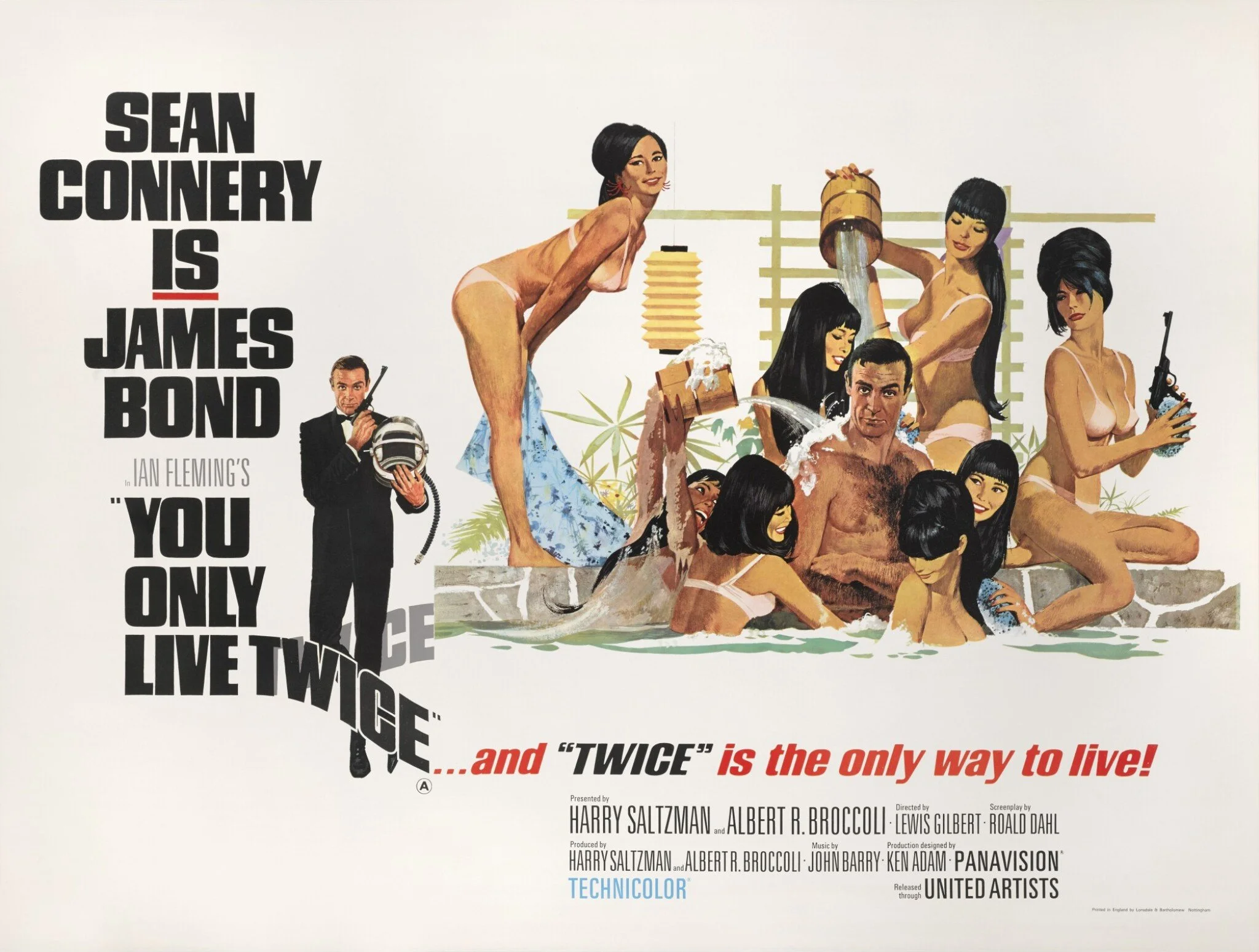

Beginner’s Bond: You Only Live Twice

I’ve loved watching movies of every variety since I was seven years old, but James Bond has always been a notable absence in my personal film canon. These “Beginner’s Bond” posts are meant to document my reactions as I watch all of the films in the 007 franchise for the very first time. Previously, 1965’s Thunderball set the bar for ridiculousness pretty high—or so I thought.

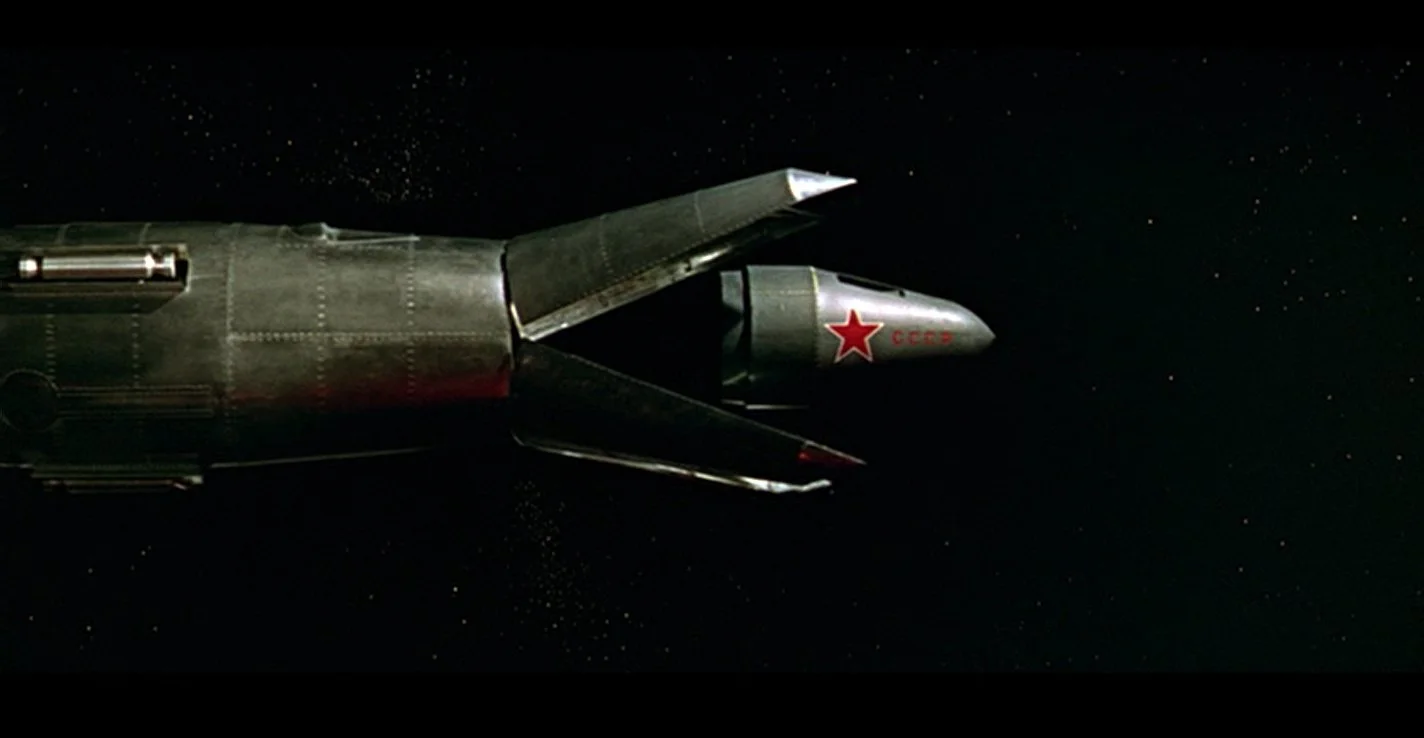

You Only Live Twice started with a spaceship swallowing another smaller spaceship, and I just knew whatever restraints the studio previously labored under had been cast aside. While the United States and the Soviet Union bicker over who is stealing whose spacecraft, the masterminds at MI6 are pretty sure the answers will be found in Japan. So naturally they send their best operative, 007 himself, to Hong Kong to fake his death so that he can swim to Japan after being buried at sea and meet his contacts at a sumo tournament. James falls through an embarrassing number of trap doors as he tries to investigate the disappearing spacecraft with the assistance of Japan’s secret service.

An assassin silences Bond’s contact, but Bond manages to kill the assassin back. Then he uses the dead man’s uniform to sneak into Osato Chemicals. There he learns that SPECTRE is brewing up tons of rocket fuel, before he is seduced/interrogated by Helga Brandt, Number 11. She locks him into his seat aboard an airplane and sets off a smoke bomb in his face before bailing out mid-flight. Of course, Bond is able to free himself, land the plane, and flee before the flaming plane explodes.

Bond discovers Blofeld’s secret volcano lair while flying around in an autogyro, which looks like the skeleton of an unfinished helicopter. He wasn’t sure until four attack choppers came after him, confirming there was definitely some supervillain nonsense going on. James goes undercover to train with ninjas and go through an unfortunate montage where makeup and eye prosthetics are applied to make Mr. Bond “look Japanese.” He’s even assigned a wife to complete the cover identity. While Kissy Suzuki proves to be a valuable addition to the team during the final battle, I’m puzzled as to why all of this subterfuge was necessary. James doesn’t use his new Japanese identity to walk into any place that was previously inaccessible to him as a white man. James, Kissy, and a small army of ninjas mount an all-out assault on the volcano lair, where he actually utilizes a different disguise—a spacesuit that completely concealed his face. 007 saves the day by preventing another spaceship from being swallowed, and self-destructs Blofeld’s imperial star destroyer before doing the same for his villainous volcano lair.

There’s just no real reason Bond needed to be Japanese for any part of this mission. I guess it’s no less ludicrous than anything else happening in this movie, but it’s a lot less fun when it’s racist. Which brings me to some of the more toxic elements that have proven to be consistent thus far. At least once a movie, sometimes more, James will force a kiss on an unwilling woman who stops resisting when she realizes she likes it… which is barf-worthy writing, and sadly, probably the inspiration for a generation of sexual predators.

Another unfortunate trend I’ve noticed in all five movies thus far—no matter where he goes, James is always assisted by a “local contact” of some variety. These locals are never white and essentially operate like manservants. They perform all manner of errands for Mr. Bond, which sometimes includes most of the real espionage work. A hotel valet is out there sneaking photos of a secret terrorist rocket-launching facility while James recons the blackjack tables or attends an entire fake wedding ceremony with his cover wife. Don’t get me wrong—when the shooting starts, 007 always acquits himself admirably. But perhaps if he did more of his own homework, so much shooting wouldn’t be necessary.

While the dated racial insensitivities were annoying, they didn’t ruin what is an otherwise fun action movie full of beautiful people saying pithy things in between explosions. Its full of classic secret agent tropes: elaborate death traps like burning planes and ponds full of piranhas, silly gadgets like the dart-shooting cigarettes, a secret underground lair, and one exceedingly well-armed vehicle. There was no superhuman henchman this time, but I loved the reveal of the cat-petting Blofeld. I had always associated that with the Inspector Gadget villain Dr. Claw—30 years ago, I had no idea this Saturday morning cartoon was referencing a movie I had never seen.

Or had I? Memories are weird. Once the ninjas began to storm the villain’s volcano lair, I realized that it was actually You Only Live Twice, not On Her Majesty’s Secret Service as I had originally supposed, that I watched in that fuzzy childhood memory of a family vacation. But OHMSS is the next stop on “Beginner’s Bond,” the first film without Sean Connery. Will it make a huge difference? I have no idea. And that’s kind of exciting.

Beginner’s Bond: Thunderball

These “Beginner’s Bond” posts are a chronicle of my maiden voyage through the James Bond films. The adventures of 007 have always been one of the most glaring omissions in my knowledge of cinematic history, but I’m slowly closing it, one film at a time. While I found the first two movies to be surprisingly grounded, Goldfinger marked the first hard turn toward the absurd, a trend I hope continues. The next stop on my tour is 1965’s Thunderball.

Right from the start, this movie comes out swinging. Both literally and figuratively. Bond has crashed a funeral, punched a woman (who was a man in disguise) in the face, and made a daring escape via jetpack all before the five-minute mark. The beginning of this movie shows a lot of promise that the rest of it isn’t always able to deliver on. Despite this initial zaniness, the movie pumps the brakes after the title sequence has rolled.

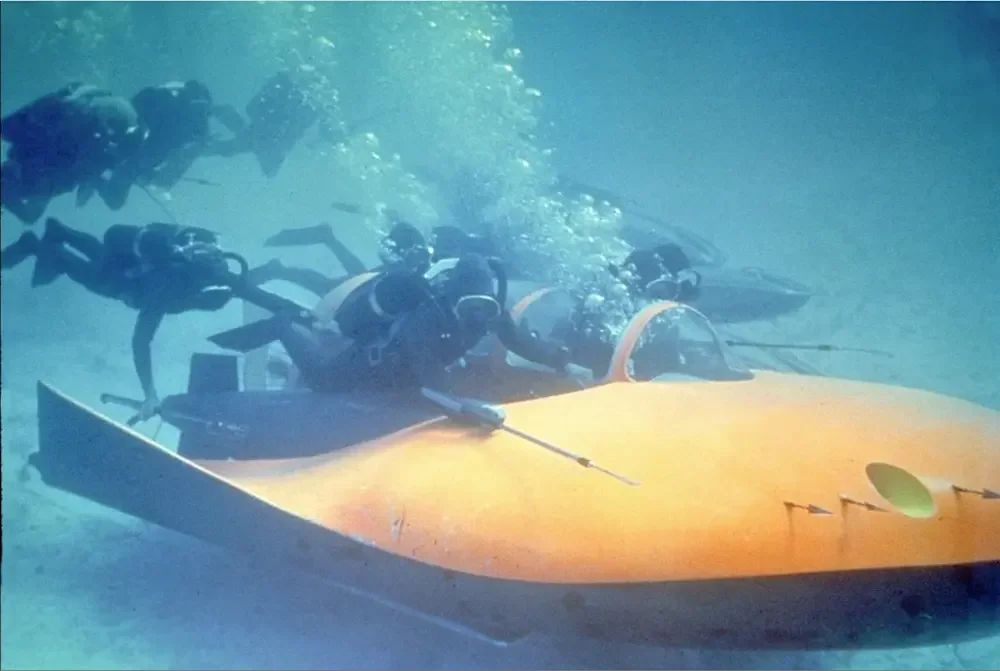

James Bond is taking some mandatory vacation time at the company spa when he randomly decides to follow a weird looking stranger and fumbles into the terrorist plot his colleagues were handling in his absence. An RAF bomber carrying two atomic bombs has been hijacked, and now the nefarious organization known only as SPECTRE demands $280 million in diamonds as a ransom, or they will nuke a major city. Since Bond is the star of this picture, he gets roped into the operation and assigned to follow Domino Derval, sister to one of the deceased hijackers. Making contact with her leads Bond to her lover, Emiliano Largo, aka Number Two at SPECTRE. When he’s not embarrassing him at one of the casino tables, Bond spends his time surveilling Largo’s property and the surrounding waters. This eventually turns up the stolen bomber hidden at the bottom of the ocean, which is enough evidence for the US Coast Guard and Navy to attack the Disco Volante, Largo’s private vessel. One amazing underwater battle later, the good guys have recovered the first bomb, prompting Largo to bail with the second one. Domino skewers Number Two with a spear gun as revenge for her brother. She and James jump just seconds before the runaway boat crashes upon the rocks.

The creators of Thunderball were no doubt emboldened by the success of Goldfinger to go as big and crazy as they could. It turns out that many tropes I have seen used and parodied often originated here, like the brutalist conference room full of villains having a business meeting about their evil empire, seen in almost every secret agent movie since. As well as the evil overlord who executes his underlings for failing to meet expectations, an idea recycled so often its become a cliche. There’s also the elaborate underwater combat engagements with armies of frogmen shooting harpoons at each other, which was parroted by most Saturday morning cartoons for at least one episode. And as far as I can tell, Thunderball started the long running gag of villainous right-hand men being called simply “Number Two.”

But despite its penchant for silly secret agent hijinks, Thunderball is a more flawed film than its predecessor. The title doesn’t make as much sense as its predecessors—“Thunderball” just the codename for the recovery operation. The music isn’t nearly as good, either. And while this movie added plenty of fun stuff to the secret agent canon, it’s also missing some elements that had become staples of the James Bond franchise. There are no real gadgets other than an underwater camera. The superhuman henchman is absent as well. It’s also pretty crazy that they introduce a jetpack at the beginning and it never comes up again, even though our hero spends a significant portion of the film conducting aerial surveillance. At one point Bond even drinks a rum collins instead of a martini!

Almost every scene, even the good ones, goes on too long. Leisurely pans across luscious landscapes pad the runtime a bit, but its mostly action scenes that overstay their welcome, stretching a clever idea until it becomes repetitive and dull. The underwater battle was cool for maybe two minutes, but it goes on for more than five. After a while, its just men anonymized by scuba gear wrestling in a cloud of bubbles. We can’t see or infer enough about this fight to know how its going moment to moment, who’s winning or losing, which makes it hard to care for very long about the quiet deaths of faceless characters we know nothing about. It’s quite rare for an action scene to be the boring part of a movie, but Thunderball managed this dubious feat. The one truly interesting conflict of the movie is between Bond and a SPECTRE agent named Fiona Volpe. For the first time, 007 is the one to get seduced and played for a fool. As she springs her trap on him, she actually mocks Bond for thinking that one sweaty night with him would bring her back to the side of righteousness. For the first time we see James bristle at rejection, lashing out by loudly asserting that it meant nothing to him. And it’s very clear that no one believes that, not even him. He later uses her as a human shield in a gunfight, which is a problematic level of pettiness.

Finally, there’s the villain. Number Two’s entire personality boils down to “guy with an eyepatch.” He’s a big evil jerk just like Goldfinger before him, but not nearly as compelling to watch. He’s not entertainingly rude or viciously sarcastic—he just has poor manners. Largo comes across like this is his first day at villainy and he really wants to make a good impression at the office. Even the shark pool feels like he’s trying too hard to have a signature thing, rather than a peculiar quirk of a singularly malicious mind. He’s not physically intimidating either, and without a henchman backing him up, it never really feels like he poses any particular threat to James Bond. There were moments in Goldfinger where 007 seemed worried he might die, but Mr. Bond never looks that concerned in Thunderball, even when he’s in the villain’s clutches. And if he’s not worried, why should the audience be? If Bond is too nonchalant in the face of danger, it will puncture any tension the story attempts to build. Which is why Thunderball is ultimately an interesting, but not impressive, film.

Thunderball is a fun procession of ludicrous images, but it’s not nearly as well-constructed as its predecessors. The film is far too long, with a poorly paced second act and a fairly lackluster finale. It’s a good movie to have on in the background while you do something more important, but it doesn’t really reward an attentive viewing. While this movie birthed a lot of hilarious tropes that will likely be alluded to time and again for all eternity, Thunderball itself is a rather forgettable film. Definitely the least interesting one so far.

Next stop on this tour is 1967’s You Only Live Twice. Hopefully it will outshine its predecessor, being both more ridiculous and more exciting at the same time. We’re only on the fifth movie. Surely it can’t all be downhill from here.

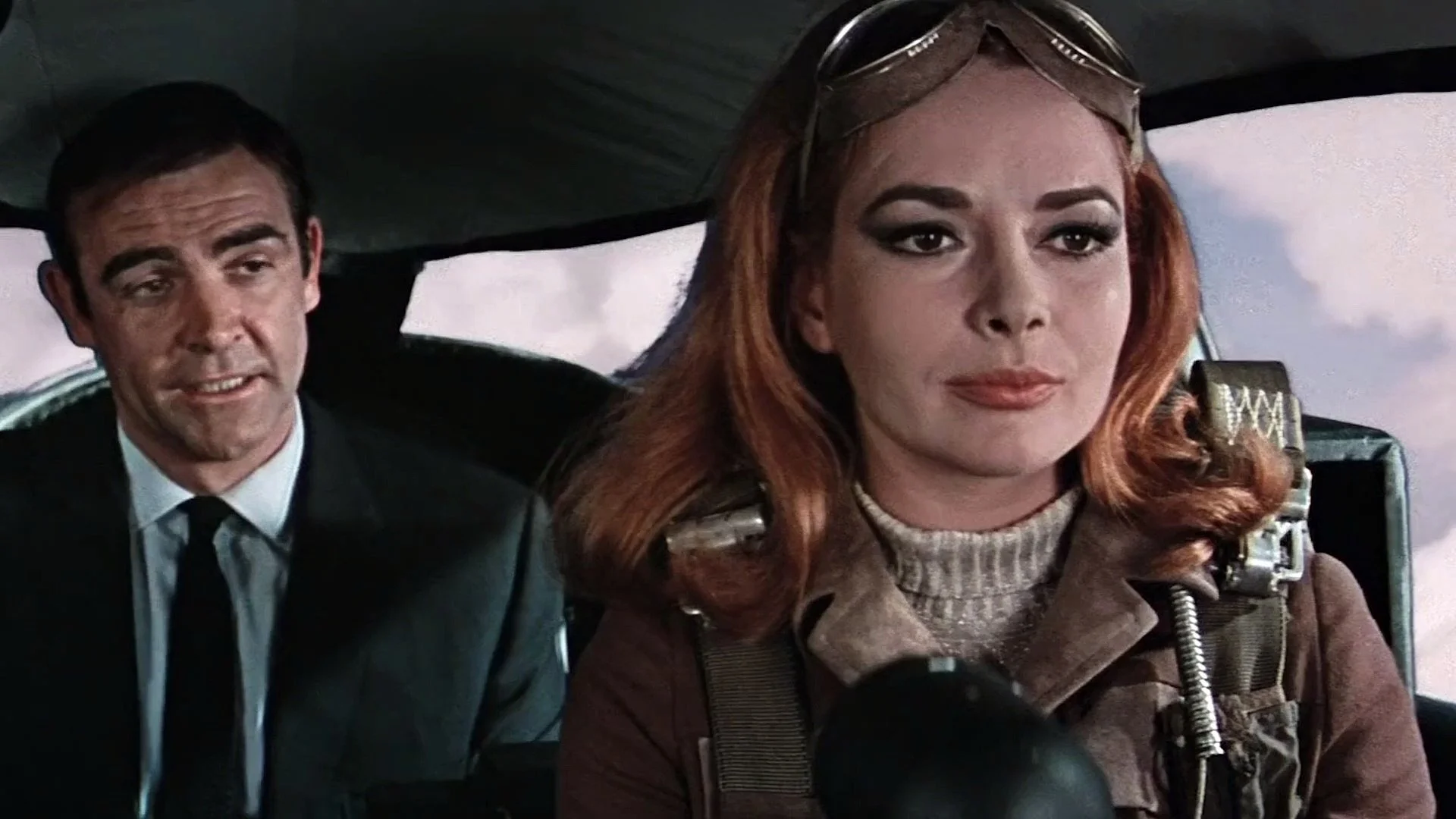

Beginner’s Bond: Goldfinger

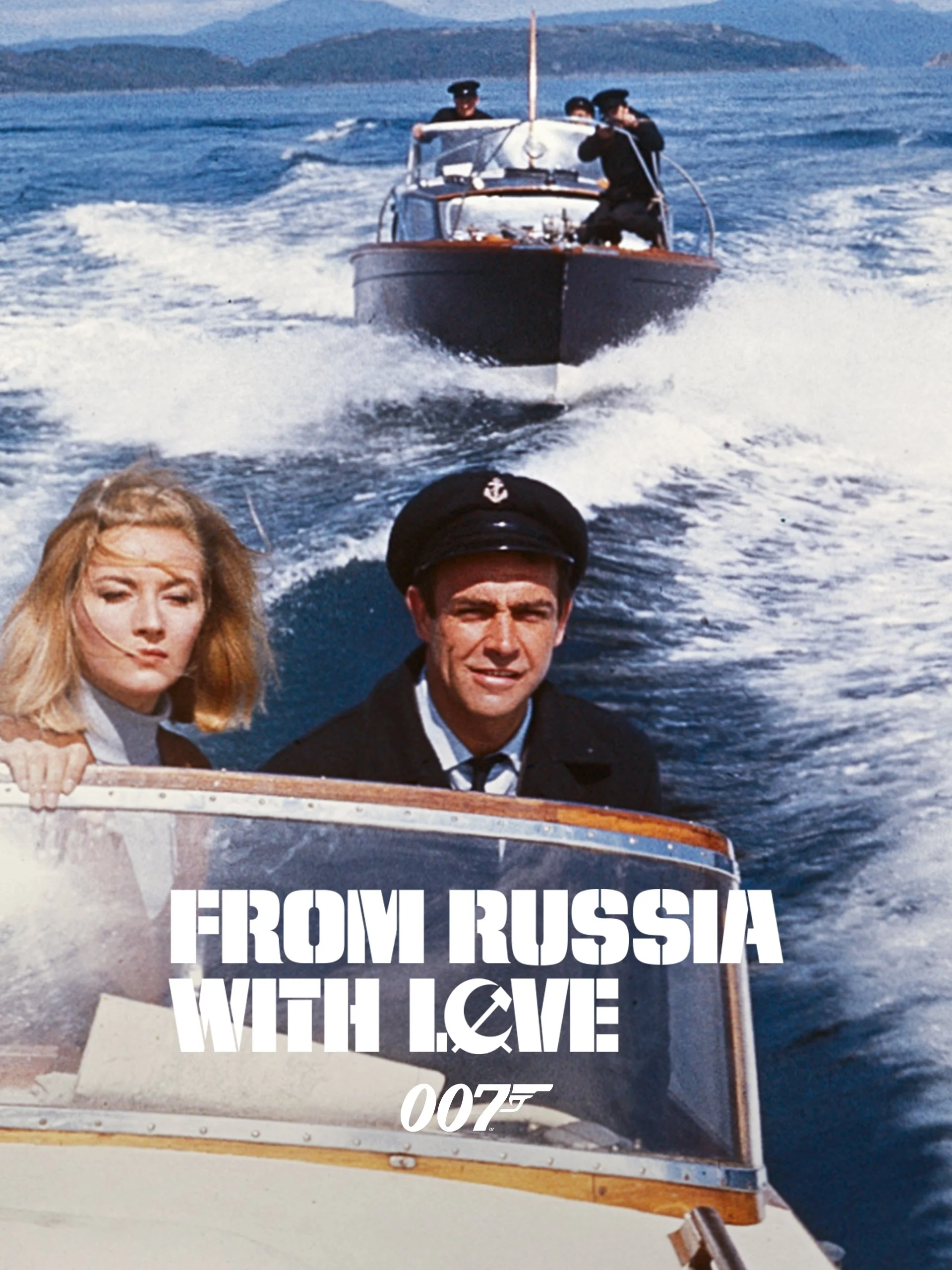

These “Beginner’s Bond” posts are about closing what is probably the largest gap in my knowledge of cinema. So I am watching all of the James Bond movies in order for the very first time, and sharing my reactions and thoughts with you, faithful readers! A quick recap—Dr. No was a pleasant blast from the past, while From Russia With Love was silly and fun despite an underdeveloped script. What does 1964’s Goldfinger have in store for me?

I found the previous two films to be surprisingly grounded, but Goldfinger proved to be significantly less interested in realism. James Bond goes to Miami to basically harass the rather literally-named shady bullion dealer Auric Goldfinger. The powers that be think Goldfinger’s up to “something,” so they send 007 to poke around in the man’s business until he gets pissed off. His mission doesn’t really have any other parameters, and he’s very good at getting under his target’s skin. Bond figures out the villain’s diabolical plan by hiding under the diorama Goldfinger uses to give his class presentation on how to break into Fort Knox. Once again, the bad guy’s right hand woman is persuaded to turn on him after a literal roll in the hay with 007. After saving the day during the siege of Fort Knox, James is invited to lunch at the White House with a grateful Unnamed President.

Goldfinger is the first functional prototype of what the Bond movies were to become: big, explosive action movies full of sexy people making playful banter as they shoot at each other. All of the elements are there. He introduces himself as “Bond, James Bond.” He orders the dry vodka martini shaken over ice. Not a single woman in the film can resist his charm, except probably the old lady guarding the evil lair’s front gate with a machine gun. In my head-canon, that’s definitely Goldfinger’s grandma sitting out there in a shack waiting to waste any interlopers that wanna try her. It would make a lot of sense. We also meet Pussy Galore, the first of a long line of Bond girls with ridiculously suggestive names.

Although Q provides fewer gadgets than in From Russia With Love, he makes up for it by rolling out the iconic Aston Martin for the first time. Fully loaded with smoke screens, oil slicks, tire-shredding spikes… there’s even an ejector seat! Classic spy stuff. At one point Mr. Bond is strapped to a gold table and nearly bifurcated by a slow-moving laser, the franchise’s first instance of the needlessly complex death trap. We also get to meet the hat-throwing mute man-mangler Oddjob, the first superhuman henchman to give James a solid trouncing or two before inevitably being outsmarted. Goldfinger ended with a massive action set piece, a shootout between two armies, which I assume became the standard conclusion for future films.

And then there is the titular villain himself. Auric Goldfinger is a fat, balding, orange-skinned billionaire with no class who cheats at golf and decorates everything he owns with a tacky amount of gold, which made him surprisingly relevant to a watcher in 2025. His plan to murder thousands of innocent people in order to make himself slightly more obscenely wealthy is also distressingly familiar. And when his master plan starts to collapse around him, he kills his own men to create a distraction that will allow his escape, which feels eerily prescient. In the end, Goldfinger gets sucked out a plane window at 30,000 feet, and we can only hope that is foreshadowing. There’s no question he set the bar rather high for future villains to clear. It’s hard to imagine an antagonist that’s easier to hate than Auric Goldfinger.

Goldfinger basically established the blueprint for a blockbuster action movie. I’m interested to see if Thunderball will follow it, but my only wish is that things continue to get more and more ridiculous.

Beginner’s Bond: From Russia With Love

In case you’re just joining us, Beginner’s Bond is a series about finally closing one of the largest gaps in my cinematic knowledge—the adventures of Britain’s top secret agent, James Bond. I’m watching all the classic films for the first time and sharing my reactions with you, faithful reader. Dr. No turned out to be a pleasant surprise. Can From Russia With Love do the same?

Pretty much everything I said about the previous film also applies to this one. It’s still fairly grounded, with a plot born from period-appropriate Cold War paranoia. James Bond is sent to retrieve and protect Tatiana Romanova, a defector from the Soviet Union. She promises a coveted Lektor code machine in exchange for safe passage to the West. Although M and Mr. Bond both call the scenario an obvious trap (because it is), they also agree that the possibility of acquiring a Lektor is worth the risk. Most of the movie is just watching Bond and Romanova travel through picturesque locations, when they’re not snuggled up in their private room making double entendres at each other. Occasionally someone tries to kill them, but other than that it’s a rather lovely vacation.

There are also some really weird choices being made here. There’s a scene where James simply looks around an unremarkable hotel room while the full orchestral theme blares as if he were in the middle of a climactic gunfight. It is puzzling that the final boss fight pits Bond and Romanova against one old woman in a small room, instead of a big explosive set piece like its predecessor. And its pretty funny that 007’s legendary lady-loving skills play a significant part in the plot this time. Romanova is convinced to abandon her assignment as a double agent and defect from the Soviet Union for real after a long weekend locked in a suite with MI-6’s most reliable stud. She never stood a chance.

From Russia With Love gives us the first proper spy gadgets. Although creative, they’re still quite practical. Fun stuff like a briefcase that conceals a small knife in a spring-loaded holster, and its booby-trapped with tear gas if you don’t open it the right way. You can tell the movie is most proud of the tape recorder hidden within a camera, as if disguising a recording device as a different recording device was a brilliant piece of tradecraft. It’s still the first thing the bad guys are going to confiscate, M!

While I certainly don’t think From Russia With Love is a better movie than Dr. No, it is more fun. This film isn’t afraid to be silly, like during Bond’s epic slap fight against Grant that demolishes the interior decor of the train. Or when Tatiana simply can’t stop begging Bond for more “attention” while he tries to take a work call. The cast isn’t always doing something important, but they are enthralling to watch all the same.

Up next is Goldfinger. I’ve heard it is a weird one. I look forward to the escalating ridiculousness.

Beginner’s Bond: Dr. No

Devout action fan though I am, I have a blind spot for a certain classic series about a British secret agent. I saw Goldeneye and Casino Royale in the theaters, and there’s a distant hazy memory of watching On Her Majesty’s Secret Service with my father during a rainy afternoon on family vacation. But for most of my life I have only known James Bond as fodder for countless parodies of snooty spies more interested in getting drunk and bedding their female colleagues than collecting any intelligence. And while that is not an inaccurate description of 007, in my estimation it is far from complete. So I’m going back to watch all the old movies to see if I’m right, and also to examine what has made Mr. Bond the most enduring cinematic hero of all time.

First up is 1962’s Dr. No. Back then it was fairly unusual for a movie to be named after the villain rather than the hero, so it already stood out as soon as you read the title. I always thought it impressive that James Bond had such an extensive career in screen espionage without ever including his name in the title of any of his movies. While we see plenty of villain-led films released in the early 21st century, they are usually ill-conceived origin stories that seek to “rehabilitate” evil characters by inventing paper-thin justifications for all of their heinous acts, as if they were running for public office rather than serving as the antagonist in a fictional story told for entertainment. But we don’t actually see the nefarious Dr. No until the third act. For most of the movie he is nothing but a menacing name that strikes fear into the locals. He finally shows up to exposition his evil scheme over dinner so 007 will know exactly how to stop him. Epic larger-than-life villainy that used to be confined to the pulp pages was now moving around and talking up on the silver screen—just one of the many influences Britain’s top secret agent has had on the history of cinema.

As a franchise that spans several eras of filmmaking, James Bond is a surprisingly reliable measure of the evolution of the typical action hero. Back in the 1960s, a movie’s leading man didn’t have to be the perfectly sculpted specimens demanded by Hollywood today. While Sean Connery was in great shape, he did not have a six-pack or well-defined biceps. He even sports a hairy chest with complete confidence, something that is practically forbidden in contemporary action movies. And ultimately, none of it matters because Connery is so charismatic that audiences would watch him do nothing but smoke and play cards for two hours—all the action is just a bonus. But by the time we reach the Daniel Craig era, Bond is just as shredded and hairless as Captain America. That swole-yet-chiseled physique makes no sense for a spy. Not only would he attract all kinds of attention, the workout schedule required to maintain that body alone would make it impossible for him to ever get any espionage done.

Dr. No introduces a lot of elements that would become standard for the franchise. James Bond is England’s most dashing and debonair double O agent. He is irresistible to women, and although he doesn’t bed all of the female characters, every single one sure does give it her best try. Bond travels around the world cosplaying as a bored millionaire. He makes his iconic introduction, orders a martini “shaken, not stirred,” and makes terrible puns after killing henchmen. We see the gun-barrel opening sequence and hear the classic theme song for the first time. He even flirts with Moneypenny on his way into the office.